What they Mean for Public Utility Returns

Kurt Strunk is Vice President of National Economic Research Associates, Incorporated. Walter Hopkins is Senior Analyst of National Economic Research Associates, Incorporated.

In the week following the 2016 presidential election, bond yields rose substantially, signalling the potential reversal of a downward trend in yields that began nearly thirty years ago. Despite this initial move, uncertainty remains as to whether long-term yields will revert to historic averages.

Policy interventions by central banks may continue to suppress yields, leading to low or negative rates. The path of interest rates will affect how regulators view the fair level of return for investors who commit their capital to utilities that provide essential services to the public.

Steve Bannon, chief strategist for the Trump White House, signalled the administration's intent to take advantage of low borrowing costs. In a recent interview, he argues, "I'm the guy pushing a trillion-dollar infrastructure plan. With negative interest rates throughout the world, it's the greatest opportunity to rebuild everything."

With this view, it appears that the administration does not expect rates to rise significantly, despite the bond market's initial reaction to the Trump presidency. However, the fiscal spending anticipated by the new administration will naturally pressure rates upwards and may not be practicable without further central bank bond purchases and interest rate suppression. Those are actions Mr. Trump spoke out against as a candidate.

Even with central bank policy support, the question remains whether the financial markets will be able to incorporate this new debt without a rise in yields, as a consequence of the administration's digging the hole even deeper.

"After 2008, the cost of equity for electric utilities fell by less than 50 basis points while Treasury yields fell by approximately 200 basis points." – Kurt Strunk

"After 2008, the cost of equity for electric utilities fell by less than 50 basis points while Treasury yields fell by approximately 200 basis points." – Kurt Strunk

This article reviews recent trends in interest rates and examines the unusual phenomenon of nominal negative interest rates, while placing the latter in the context of the theory of capital and interest. We highlight several rate drivers that, after the recent election, could lead to yield movements upwards or downwards, and even into negative nominal territory.

We then analyze how such policy and market developments could affect the analyses used to establish public utility returns and expert debate in adjudicated rate cases.

Recent Trends: Unprecedented Policy Interventions Lead to Negative Nominal Rates

After the 2008 financial crisis, the decline in interest rates accelerated and far exceeded analysts' expectations. In some markets, nominal long-term interest rates even turned negative, a phenomenon that turns upside down the traditional model of capital and interest. In that model, the issuer pays investors for the privilege of using their money for productive purposes.

In practical terms, a nominal negative interest rate means that investors receive no compensation and instead pay the issuer of the bond for the privilege of parking their funds. While in the United States, nominal interest rates have not yet fallen below zero, real interest rates have.

"In the face of even more atypical conditions, Return on Equity experts will need to continue to sharpen their pencils and scrub the oft-conflicting signals from capital markets." – Walter Hopkins

"In the face of even more atypical conditions, Return on Equity experts will need to continue to sharpen their pencils and scrub the oft-conflicting signals from capital markets." – Walter Hopkins

Abroad, negative interest rates have become common. Nearly twelve trillion dollars of bonds traded at negative nominal yields at the time of the November elections and even more traded at negative real yields.

Following the financial crisis of 2008, the U.S. Federal Reserve took unprecedented steps intended to stimulate the economy. These included the purchase of toxic mortgage assets, securities based on pools of mortgages unlikely to be paid, to shore up bank balance sheets. Other actions included the purchase of government bonds and setting targets for short-term interbank lending rates at levels close to zero.

Over the five years that followed, the U.S Federal Reserve carried out three phases of asset purchases, also known as quantitative easing. Through those purchases, its balance sheet expanded by over four and a half trillion dollars. It held the short-term rate target at close to zero for eight years. Taken together, these actions represent a massive and unprecedented stimulus program, whose long-term effects have yet to be seen.

Importantly, the U.S. Federal Reserve did not act alone. Central banks across the globe pursued similar policies, implementing six hundred and sixty-six interest rate cuts since the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy.

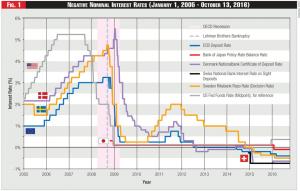

Figure 1 - Negative Nominal Interest Rates (January 1, 2005 - October 13, 2016)

Figure 1 - Negative Nominal Interest Rates (January 1, 2005 - October 13, 2016)

Japan had begun its stimulus program in the form of near-zero interest rates a decade before the crisis. That country acted aggressively to expand it as economic conditions weakened during the crisis. The result in Europe and Asia, where central banks have taken more aggressive steps than the U.S. Federal Reserve, has been the pricing of many government and corporate bond issues at negative nominal yields.

While negative nominal interest rates may be unlikely in the United States, they are not implausible, given these developments in Europe and Asia.

Figure 1 shows the five central banks that have adopted a policy of targeting negative nominal interest rates as compared to the target rate in the U.S. Although the U.S. Federal Reserve has not lowered the nominal level of the federal funds rate below zero, it is negative on a real basis.

See Figure 1.

Figure 2 - Negative Nominal Sovereign Yields, October 18, 2016

Figure 2 - Negative Nominal Sovereign Yields, October 18, 2016

As shown, the central banks of the European Union (Euro), Japan (yen), Denmark (krone), Switzerland (Franc), and Sweden (krona) have all brought the interest rate for holding depository institution funds below zero percent. In other words, large banks must pay the central bank for the right to deposit money.

Because depositing money with the central bank is a privilege only afforded to the most creditworthy institutions, the rate assigned to the deposits can be viewed as the base rate. That is the rate upon which all other interest rates in the economy are set.

Additionally, when a central bank sets a low interest rate, the central bank signals to the market that it foresees a weak economy and low inflation. Such monetary policy action directly influences interest rates by influencing depository institutions' incentive to deposit money with a central bank as compared to seeking riskier investments in the economy. And monetary policy can indirectly influence interest rates by signalling the central bank's outlook on growth and inflation.

In addition to fixing short-term rates, central banks have employed a more direct tactic for affecting long-term interest rates: so-called quantitative easing. Through this, the central bank actively buys and sells bonds, directly affecting the market prices for bonds and the associated interest rates. The central bank must be a large buyer to make a material difference on the overall level of interest rates.

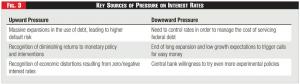

Figure 3 - Key Sources of Pressure on Interest Rates

Figure 3 - Key Sources of Pressure on Interest Rates

With aggressive monetary easing and quantitative easing, many central banks have achieved largely negative yield curves on sovereign debt as shown in the figure. For the ECB, German sovereign debt is shown.

See Figure 2.

In the next section, we explore what prolonged negative nominal interest rates mean for investors from a financial economics perspective.

Theory and Practice: The Mystery of Negative Interest Rates

The Time Value of Money: Implicit in the neoclassical theory of capital and interest is the assumption that investors require a positive rate of interest. That compensates them for deferring consumption and for not deploying their capital to other productive endeavors.

The act of deferring consumption requires compensation because satisfaction of present wants and needs is more valuable than that of future wants and needs. Similarly, from the decision to forego other investments that yield positive returns, an opportunity cost is born that bounds the level of interest required by the investor.

For academics and practitioners alike, a troubling aspect of negative interest rates is the dearth of economic theory addressing the subject. In the words of famed investor Warren Buffett, "What has happened with interest rates is really extraordinary."

"You can go back and read everything that Keynes wrote, and everything Adam Smith wrote, or Ricardo wrote, or Galbraith wrote, or you name it, Paul Samuelson - you won't see a word, in my view, about sustained negative interest rates. We are doing something the world hasn't seen. It distorts everything. We do not know how this movie plays out."

Nowhere in the neoclassical theory is the notion that investors might agree to pay to make investments rather than be paid. There is no evidence that future consumption is more valuable than current consumption. As a result, the increasing prevalence of negative interest rates seems to many financial analysts counterintuitive and impossible.

Surely, if investors have to pay to hold bonds, they will not buy them and instead hold cash. However, deflationary conditions, subtleties in how large investors operate and constraints on the holding of cash may result in negative nominal interest rates that can be tied to a plausible explanation.

The Importance of Inflation Expectations: In his 1906 treatise The Rate of Interest, the economist Irving Fisher dissects the nominal interest rate into two components: the real interest rate and the expectation of inflation: Nominal interest rate=Real interest rate + Inflation expectation.

From this relationship, it is evident that nominal rates can turn negative in an economy experiencing deflation when the expected rate of deflation exceeds the real interest rate required by investors. Expectations of significant deflation offer one potential explanation for the recent trend of negative nominal rates in some markets.

Holding Costs and Other Constraints on Large Investors: Other explanations exist as to why interest rates may turn negative. Consider, for example, the possibility that the cost and risk of holding cash could exceed the small-but-positive returns that investors otherwise require in times of easy money. In such a case, the negative interest rate would simply reflect the degree to which holding costs exceed investors' required rates of return.

To hold physical cash, one needs a secure safe. Additionally, insurance would be needed to put the risk of holding of physical cash on par with holding a government bond, whose principal is as safe as the government issuer.

If the price paid for the safe and insurance is more than the negative interest earned, it will be cheaper to earn negative interest than to hold cash.

Also, certain institutional investors such as regulated insurers have strict rules governing the securities in which they can invest. For example, some have rigid asset allocations and a requirement to buy bonds of certain ratings.

Strict compliance with those rules likely causes these market buyers to invest irrespective of the price of the bonds. That may explain who's buying the negative yielding securities.

Market participants may also be anticipating the purchase of the bonds by central banks. They may simply be taking a temporary position at one negative yield with the hope of subsequently selling the bond at a higher price with more negative yield and booking a profit.

Over time, however, we would expect these investors to adjust their strategies and asset allocation rules to avoid taking on risky investments that they must pay to invest in.

Restrictions on Holding Cash: The final explanation we consider here for why interest rates can turn negative is the potential for a restriction on holding cash. Several governments in Europe have made the development of a cashless society an explicit goal and have taken steps to make that a reality.

In markets where individual investors are restricted from holding cash, and thus have no obvious way to pull their money out of the financial system, it is plausible that these investors will simply be captive to the level of prevailing rates, positive or negative.

Future Rates: Market and Policy Dynamics

Price formation in the government bond market is complex and depends on a wide range of factors. It has generally been the case that markets set long-term interest rates, not policy makers.

However, the actions of multiple central banks in the period since the 2008 financial crisis have made clear their intent to wield control over more than just short-term depository rates. The stronger of these sometimes opposing forces will determine the path of interest rates. In the figure, we summarize key sources of pressure, both upward and downward.

See Figure 3.

Massive Expansions in the Use of Debt: Persistent low or negative interest rates encourage the assumption of debt, as the new administration's intent to take advantage of low or negative interest rates suggests. Global gross debt in the nonfinancial sector has soared as interest rates declined.

Since 2000, global gross debt has more than doubled to a hundred fifty-two trillion dollars in 2015, as highlighted in a recent report by the International Monetary Fund. We observe the same trend for non-financial corporations in the U.S., whose debt has increased by fifty percent since 2009, and logically so, as low rates have made more projects economic.

The market consequences of the higher debt levels are naturally upward pressure on yields as default risk grows. However, running counter to that, political pressure to suppress rates will increase as the cost to service the debt rises.

High interest costs will stress the federal budget and will likely trigger fights over the debt ceiling. Higher yields may therefore translate into calls for new policy tools and further interest rate management by government.

As noted, the success of the infrastructure spending planned by the Trump administration may depend on the continuation of quantitative easing by central banks. If so, the central bank balance sheets would need to absorb the debt and other market participants would need to retain confidence in the U.S. government for rates to remain low (or negative).

Diminishing Returns, "Pushing on a String": Quantitative easing has diminishing returns with regard to its ability to stimulate the economy. During quantitative easing, the central bank purchases bonds from investors (banks) in the hope that they will then deploy that cash into alternative investments that will meaningfully stimulate the economy.

At a certain point, however, the opportunities for deployment of that capital dwindle, thereby limiting the stimulative effect of quantitative easing. Ray Dalio, Bridgewater Associates founder and frequent government advisor during the 2008 financial crisis, uses the metaphor of pushing on a string. That's a phrase often attributed to John Maynard Keynes, used to describe the diminishing returns associated with quantitative easing.

Further, when central banks bring interest rates to their lowest levels, they neutralize the mechanism governments use to respond to recessions: lowering interest rates. Respected bond investor Bill Gross wrote in August that the primary problem in the economy lies with zero/negative interest rates because they fail to provide an 'easing cushion' should recession come knocking at the door.

Recessions are often short-lived because the over-accumulation of debt can be relieved by the central bank lowering interest rates. However, if interest rates have been driven near zero or even into negative territory, then the debts must be unwound through a painful deleveraging.

Economic Distortions: Aside from the pushing on a string effect resulting from persistent quantitative easing, persistent low or negative long-term interest rates cause other, more visible, economic distortions.

In the face of negative interest rates, companies are charged for the money they hold in banks. As Warren Buffett described in a recent interview, the result is that companies would actually prefer not to collect their receivables.

"A billion Euros at -0.35 percent [then it is costing us] $3.5m Euros per year just to have that. Well, that means that you don't want to collect your receivables. Why would you want to collect your receivables?"

Hence, an environment of negative interest rates can undermine traditional business management assumptions.

And negative interest rates encourage institutions to remove holdings from the financial system, since investors will be better off putting cash under the proverbial mattress rather than in a bank. Munich Re, a Berkshire Hathaway reinsurance holding, converted its short-term loans to cash in vaults to avoid negative interest rates, but doing so is not an easy decision. Institutions in the position of Munich Re must weigh the logistics and insurance costs of holding physical cash.

Need to Manage Cost of Federal Debt: At the government level, since George W. Bush's entry into office in 2001, the national debt expanded from $5.73 trillion to $19.8 trillion, an increase of two hundred fifty percent.

With the prevailing low interest rates, the current cost of interest on the nearly twenty trillion dollars in U.S. debt is only $0.5 trillion. However, if interest rates rise, the cost of servicing the U.S. government debt will increase accordingly.

An increase from the current two and a half average interest cost to five percent interest cost, even if such a change occurred gradually, would result in the doubling of interest payments to a trillion dollars.

Experimental Policies: In many ways, the steps taken by the U.S. Federal Reserve mirror those taken by the Bank of Japan and certain central banks in Europe. If the U.S. Federal Reserve continues to follow the policy leads of Europe and Japan, such action may lead the United States into negative nominal interest rates.

One recent policy intervention pursued by the Bank of Japan is yield curve management. The Bank of Japan has taken overt efforts to steepen the yield curve, a form of yield curve management that relies on quantitative easing.

Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen noted in a recent speech that she would consider direct purchases of stocks as an alternative, experimental policy should conditions warrant it. The Bank of Japan itself has been a large buyer of Japanese stocks and is currently the largest shareholder in companies in the Nikkei Index.

In addition, many have cited the potential progression towards what is called helicopter money, which could be implemented in different ways to counter the diminishing returns associated with monetary policy stimulus. Direct fiscal spending would constitute one form of helicopter money.

In sum, it is certainly plausible that the U.S. Federal Reserve could continue with experimental stimulus programs.

Fair Returns for Utility Investors

Establishing a fair return can be one of the most contentious elements of a public utility rate case. Since the financial crisis, extraordinary policy actions by the U.S. Federal Reserve and other central banks have led to important changes in the capital markets.

In the face of these policy actions, FERC has found that these capital market conditions are atypical. Nevertheless, some parties to public utility rate cases contend they are not atypical and instead reflect a new normal. The future path of interest rates will of course determine whether such arguments can still credibly be made.

In this section, we recap how policy interventions by central banks have affected the metrics used by financial analysts to assess fair utility returns. We then analyze three potential paths for interest rates. We show how those paths could affect the dynamic in the hearing rooms of regulatory commissions across the country and the fair returns they award to public utilities.

Reach For Yield: In financial markets, where fixed-income securities are returning historically low yields reflecting suppression attributable to central bank intervention, a reach for yield has pushed more and more investors into riskier assets such as stocks, driving the equity markets to new heights.

In this context, utility stocks have attracted more investors than are typically interested in utilities. Financial analysts predict that when yields return to other investment alternatives, these hot-money investors will flee utility stocks, resulting in a repricing of sector equities and higher implicit internal rates of return.

The temporary parking of funds in utility stocks has led to conditions where Discounted Cash Flow and other models will not necessarily capture the requirements of long-term investors in utility stocks. That will be the case unless one accounts for changes in future interest rates if and when such parking ends.

Volatility and Asymmetric Downside Risk: Equity markets have exhibited spikes in volatility as the level of interest rates has declined. These bouts of volatility have made equity investing riskier.

Further, as a result of high price-to-earnings multiples and the pushing-on-a-string effect, some investors perceive an asymmetric downside risk associated with equity investments. For example, Ray Dalio of Bridgwater Associates notes: "The risks are asymmetric on the downside, because asset prices are comparatively high at the same time there's not an ability to ease. That asymmetric risk exists all around the world. So every country in the world needs an easier monetary policy."

Higher Equity Market Risk Premiums: After the financial crisis of 2008, yields on long-term Treasuries fell precipitously, yet the cost of equity did not track this decline basis point for basis point.

The cost of equity for electric utilities, as measured by the Return on Equity awarded in adjudicated proceedings, fell by less than fifty basis points while Treasury yields fell by approximately two hundred basis points. Some Return on Equity models can be implemented to capture this trend, but others are not structured to do so explicitly.

Plausible Paths for Long-Term Rates: We now turn to our analysis of three plausible paths for long-term interest rates and examine how those paths will shape debates in adjudicated rate cases across the country.

A. Scenario 1: Bond market reprices risk and long-term Treasury yields rise above five percent

Following the 2016 election, several respected investors such as Stanley Druckenmiller of Duquesne Capital and Jeffrey Gundlach of DoubleLine Capital predicted long-term Treasury yields will rise to six percent within one to five years.

Interest rates in Scenario 1 would approach a more natural market-based long-term interest rate and would render discussions of negative interest rates moot. Possible distortions in the equities markets resulting from interest rate management by the U.S. Federal Reserve and other central banks and investors' reach for yield may dissipate.

The so-called hot-money investors would flee utilities as many have anticipated. Discounted Cash Flow models might not suffer from improper assumptions about the permanence of slightly positive interest rates. Trading in the bond markets during the first week after Mr. Trump's election suggests this path is a contender.

B. Scenario 2: Long-term Treasury yields continue to move lower and tread into negative nominal territory

Scenario 2 represents the continuation of managed long-term interest rates with significant policy interventions. In the rate case hearing room, if this scenario were to unfold, those who claim interest rates have found a new normal would cite the continued low or negative rates as further evidence of normality.

Similarly, there will be others who understand that such rates are made possible by central bank intervention and require continued intervention in the capital markets. Those witnesses will stress that conditions have become even more atypical, citing the counterintuitive phenomenon of negative rates.

In the face of even more atypical conditions, Return on Equity experts will need to continue to sharpen their pencils and scrub the oft-conflicting signals from capital markets. Traditional utility ratemaking models rely upon the relationship between interest rates and equity returns. But some cannot explicitly capture higher risk premiums required by investors.

Since the traditional ratemaking models do not account for this atypical economic environment, it is likely that the FERC would continue to use an alternative approach, as it did in Order No. 531. And that state commissions would implicitly recognize the need to address the massive policy interventions when determining fair returns.

C. Scenario 3: Long-term Treasury yields begin to rise but get stuck somewhere around three to four percent

This is a scenario in which the market prices reflect some expectation of continued intervention, while recognizing the limits on how far such intervention can go. For utility rate cases, it is an ambiguous scenario, likely to trigger the same Return on Equity debates of the past several years.

In this scenario, although long-term rates have risen somewhat, short-term rates are likely still to be very low and may be negative in real terms. The existence of negative real interest rates would be evidence of anomalies in capital market pricing. That would offer further support for the modified approaches taken by entities such as FERC to assure fair returns in such an environment.

Conclusion

Sustained negative interest rates have appeared throughout parts of the world. A sustained negative interest rate environment is not contemplated in textbooks and presents a variety of practical difficulties in the economy. As Warren Buffett puts it, "we do not know how this movie plays out."

A clear driver of the sustained negative interest rates in this economy and sustained near-zero interest rates in the United States is never-before-seen central bank intervention.

Understanding the mechanics of the intervention, such as the purpose and effect of the U.S. Federal Reserve funds rate and quantitative easing, is instrumental to understanding the risks faced by investors in the current climate. Investors have identified new risks stemming from the natural limits of quantitative easing, such as the pushing-on-a-string effect.

How does this atypical environment impact utility rate cases? Many traditional utility rate case models are inadequate in this environment. The inadequacy of the models has been recognized in a variety of rate cases before FERC and state commissions.

If rates continue to rise in the wake of the Trump election (Scenario 1), this challenging spell for utility rate models will be a flash in history. If, however, rates fall further (Scenario 2) or continue to remain low due to central bank intervention (Scenario 3), then utility ratemaking will require modified approaches to assure fair returns.

Lead image © Can Stock Photo / duha127