Out of Sight, Out of Mind

Charles Bayless recently retired as President and Provost of the West Virginia University Institute of Technology. Previously he was Chairman, President, and Chief Executive Officer of Illinova Corporation and its wholly owned subsidiary, Illinois Power Company. Prior to joining Illinova Corporation, he was Chairman, President, and Chief Executive Officer of Tucson Electric Power Company.

In 1992, I authored a paper in Public Utilities Fortnightly entitled "Natural Monopolies Accepting the Truth." It argued the economic factors underpinning our industry had so fundamentally changed that the entire generation segment should be deregulated. I was wrong. There are too many externalities for total deregulation.

Externalities were first identified by Arthur Pigou in his work "The Economics of Welfare." An externality is a cost or benefit resulting from a transaction. But the cost or benefit is incurred by a third party who is not a party to the transaction. And for such cost or benefit, no market exists.

An example of an externality is where company A produces a chemical and sells it to company B. In the process A discharges a byproduct chemical into a river, harming the people downstream who were not parties to the sale.

As no market exists for this pollution, the market cannot work. The downstream people have no way to stop the discharge except through political action and regulation.

Let the market handle it, is not an option where externalities are involved. By definition, there is no market.

Figure 1 - Private, Club, Common and Public Goods

Figure 1 - Private, Club, Common and Public Goods

In the early days of our nation, externalities were limited and usually localized. What a farmer did on his or her farm did not usually affect others.

As our industrial society grew, the effects and geographic dispersion of externalities became larger and more unacceptable. Air pollution, water pollution, child labor (preventing their education), and monopolies (raising prices), imposed huge externality costs. Society realized markets did not provide self-regulating mechanisms for these costs. And so, we adopted regulation.

Markets are absolutely the best system we have for the allocation of scarce resources. Markets can optimize anything for which there is a market better than regulation.

But externalities, by definition, have no market. As society grows more complex, and as global externalities are growing, their costs are quite real. These costs cannot be ignored. They must be included if we are to reach an overall optimum.

As we deregulate and simultaneously transform our industry to renewable energy, it is fragmenting into different segments. Companies old and new operate in these segments.

But the grid is a single entity. What a company does in its segment can impose costs or benefits to companies in other segments.

For instance, a rooftop solar company may cause the incumbent utility to incur costs for backup, balancing and VAR support. Or two companies buying and selling power can cause loop flows through a third company.

These costs and benefits are externalities. The market cannot solve them. They require regulation. As our industry continues to fragment, externalities may become one of the largest products for many companies.

We have a duty to society to achieve a transition to the lowest cost energy future. Deregulation and the market are doing a great job in laying the groundwork for this transition. It is incenting companies to structure their business plans to enter almost every facet of the energy business, driving down costs, and increasing product diversity and availability.

But the costs they are driving down are only their costs. They cannot see, and may not even be aware of, the externality costs they impose on others, which may be greater than their cost savings. Thus, regulators must step in to either regulate, tax or design markets to handle these externalities, to reach an overall optimum.

Ignoring externalities led us to fossil fuels. Ignoring externalities as we transition to a deregulated market, competition and renewables will lead us to a higher cost system than is achievable by considering all costs.

Schumpeter

In 1942, Joseph Schumpeter advanced the study of the effects of externalities in his book "Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy." Schumpeter pointed out that some costs or benefits could be concentrated on one group, while others could be widely dispersed, leading to very different costs or benefits per person.

Suppose the costs of pollution are spread across society, leading to a low cost per person. And the costs of cleaning up the pollution are concentrated on the polluter.

This is the concentration of cleanup costs on a few, and the dispersion of externality costs on others. It tends to drive those on whom the costs are spread towards political action. It tends to lull those on whom the costs are concentrated into inaction.

In the example, the polluters and their employees flood legislators with dire predictions of economic doom, and petition drives to keep their plant open. This, from a pure economics point of view, is rational action.

I have had the privilege or good luck to have lived through the greatest period of environmental regulation in history. Each individual environmental regulation was accompanied by howls of protests and predictions of the demise of the affected industry; most of which never materialized. But the world is far better off. Overall societal costs are far lower as the public gains from reducing externality costs, which far exceeded cleanup costs.

Public, Private, Common and Club Goods

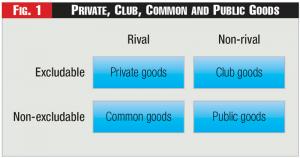

The next major advance in the study of the distribution and concentration of costs, benefits and externalities and their impact then came from the famed MIT economist and Nobel Laureate, Dr. Paul Samuelson. In his 1954 paper "The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure" he introduced the concepts of excludable and rival goods.

A rival good is when one person can use it while another cannot. If Sally eats a hot dog, Jim cannot.

An excludable good is when a person who has not paid for it can be prevented from using it, such as a movie. The possible combinations of excludable, non-excludable, rival and non-rival goods are shown in Figure One.

See Figure One.

First, we have private goods. Like Sally's hot dog, they are both rival and excludable.

Second, we have club goods. They are non-rival and excludable. Millions of people can enjoy a movie without diminishing the enjoyment of others. And it is excludable, neglecting piracy.

Third, we have common goods. They are rival but non-excludable. Consider a fish in the ocean. I can't keep you from catching it; so, it's non-excludable. But once you catch it, I can't; so, it's rival.

Fourth, we have public goods, such as air. They are non-excludable and non-rival.

Where transactions fall in this classification helps to determine how the costs and benefits of the transaction are distributed. And how markets handle or don't handle these transactions. Television companies fundamentally changed their business model when they went from non-excludable - broadcast free over the air - to excludable - cable.

Where goods fall in this classification also determines whether the market can work or whether regulation is required. Consider the tragedy of the commons.

As pointed out above, fish are common goods, rival but non-excludable. Let's look at the effects of this economic distinction on the tuna industry.

Tuna are non-excludable. Many people fish for tuna, and the number of tuna decline. Tuna becomes scarcer and prices rise. That makes it more profitable to catch tuna, resulting in more people chasing tuna, with more sophisticated equipment, which further drives down the number of tuna, raising prices even further.

Soon fishermen are using spotter planes to search for tuna. Before long, tuna could be extinct. The market cannot solve this problem. Tuna extinction is an externality. Only regulation through catch quotas, or other mechanisms, can.

This brings up another important point about markets which may shock the let-the-market-handle-it advocates. The economic incentives generated by the market are not always correct, as the market does not recognize externality costs.

Unfettered market forces would drive tuna to extinction. The market is solely maximizing the wealth of the individual fisherman, not the world as a whole. That's an externality.

Those who campaign on reducing regulations should realize that many regulations are implemented to regulate externalities. If they are repealed, there will be no way to regulate the externalities as the market, by definition, cannot.

There is no better example of this than the effort to address climate change and ocean acidification. Both result from the burning of fossil fuels.

Climate Change and Ocean Acidification

The science one needs to understand ocean acidification can be found in a high school chemistry book. The tables there show how the amount of gas dissolved in a liquid varies as a function of the solubility of the gas, the partial pressure of the gas and the temperature of the liquid.

Climate change requires a college freshman physics book. The Stefan-Boltzmann equation is usually not in high school physics texts. The science behind ocean acidification and climate change is unquestioned and trivial. The effects both will have on civilization are catastrophic. Yet, we seem paralyzed to act.

To understand why we can't seem to act, we must realize that carbon dioxide is a public good. It is non-rival. Everyone, unfortunately, gets to share it. And it is non-excludable. Everyone must share the effects. You can't opt out. Let's look at what that means to us, and more importantly to policy makers.

Assume Phoenix becomes a zero-carbon economy. It even uses solar power for backyard grills. Assume this adds seven cents per kilowatt-hour to the average electric bill.

Assume however that the benefit to society is much larger, say twenty-one cents for every kilowatt-hour saved due to the decrease in pollution. Our Phoenix consumer asks the question, how much do I get back for my seven cents per kilowatt-hour.

Unfortunately, as pointed out above, carbon dioxide is a public good. There is no way to build a climate wall around Phoenix, and have no climate change in Phoenix, while the rest of the world roasts.

Being non-excludable and non-rival, the seven cents per kilowatt-hour benefit is shared by roughly seven billion people. The Phoenix consumer, along with the rest of humanity, receives a benefit of one-billionths of a cent for each seven cents of cost.

Hardly a viable cost/benefit analysis, even for the most ardent environmentalist. Although, to society, the benefits from the reduction, twenty-one cents per kilowatt-hour, are greater than the cost, seven cents per kilowatt-hour to the consumer.

This cost-benefit disparity points out another problem, free riders. A free rider thinks, if I spend money and no one else does, I have wasted money as the problem won't be solved. On the other hand, if I don't spend money and everyone else solves the problem, I will share in the benefit as it is non-excludable. So, I'm not going to spend the money, unless I know everyone else will.

Externalities require regulation as they have no market. They also require regulation to prevent free riders.

In the age of globalization, the problems for policy makers become much more difficult. The benefits and costs are not only differentially spread over their constituents. They are differentially spread over the whole world and on future generations.

If a nation becomes a free rider, its products and services will be cheaper. It will win in the competitive market. Just as with individuals, only regulation will solve the problem. But no system of effective multi-national regulation yet exists.

Net Metering and Externalities

A great example of the externalities problem is net metering and rooftop solar. The problem arises as we deregulate our industry, and as companies operating in one niche impose externality costs on others.

Installing rooftop solar imposes costs on incumbent utilities for reserves, balancing, VAR support, and frequency support. These costs are externalities and cannot be optimized by the market, as there is no market.

Rooftop solar companies have a duty to their shareholders to maximize profits, are generally professionally run, and optimize their niche well. But optimizing individual companies or components does not lead to overall system optimization.

To consider such piecemeal optimization, let's optimize the individual components in the human body. The heart starts to beat as fast as possible. The adrenal gland starts to pump out adrenaline as fast as possible. It would be very clear to the person undergoing such a piecemeal optimization, in the two or three minutes they had left to live, that this is the opposite of an overall system optimization.

What went wrong? We neglected an externality, premature death. To achieve an overall optimization, we need to optimize the overall system, not the individual parts. This requires some components to be de-optimized.

We have an absolute duty to switch to renewable energy. But the market cannot optimize the system due to the high number of parties, the externalities, the ease with which they flow through the grid, and lack of price signals.

Regulators must retake control. Such as by least cost planning, integrated resource planning, constructing a market to internalize costs of VAR support, increased reserves, frequency control, increased likelihood of N-1 violations, etc.

Internalize, here, means calculating the costs imposed on the system by all types of generation, and then designing rates to accurately insure that each customer and producer pays their fair share of these costs. Only then can the market work.

In such an environment, net metering customers may still zero out their energy charge. Though they would still pay a demand charge reflecting the cost of transmission, backup, voltage and frequency support, and other items.

We may find that, if all costs are considered, central station solar, wind and the grid win over rooftop solar. Or that solar plus storage are better than wind. Or ... any of a thousand different combinations.

But we will never know the overall optimum configuration. Unless we either internalize the externality costs, and let the market work, or consider all the costs though regulatory proceedings.

This does not mean going back to full regulation. Regulators can design a market for externality costs as they have done for sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides.

It is important that the entities which cause the cost to be incurred must pay for the remediation. If the proper entity does not pay the cost, price signals are worthless. We already bill large customers which cause power factor problems, for example, if they have power factor out-of-tolerance.

We can follow the lead of the Ontario Power Authority as it designed the Ontario Decarbonization Plan. The OPA did a very through plan which specifically included externality costs, the optimum place, type and amount for wind, solar, backup generation, and other things.

The plan took advantage of existing assets, minimized the overall system cost, and when the plan was complete, the OPA put the components out to bid to let the market work. Ontario used regulation to handle externalities, as regulation was superior to the market. And Ontario used the market to choose the cheapest way to address the cost, as the market was superior to regulation.

Contrast this with Germany, where a feed-in-tariff was established. Producers quite naturally located plants where they would maximize their profits and neglected the externality costs of extra transmission, system stability, and other requirements. This imposed huge unnecessary costs on the German economy.

Conclusion

Schumpeter began chapter four of his book with the words, "Can Capitalism Survive? No, I do not think it can."

He reasoned that politicians would increasingly hear only from people upon whom costs were concentrated and would be unable to balance the costs and benefits for the overall good of society. They would increasingly be forced to focus on minimizing the costs affecting their constituents.

This effect is not trivial. Consider the fate of a politician in the coal fields of West Virginia who gave the greatest, most well-reasoned speech in history on voting in favor of mandatory reductions in carbon due to climate change and ocean acidification concerns.

As our economy becomes more complex and global, we will be faced with increasing externalities and differences in their distribution and concentration. This will drive even further political polarization.

Compounding the problem is that, with today's global economy, the costs of externalities are distributed worldwide. This makes solutions practically impossible.

Consider the Maldives. Its highest point is just a few feet above sea level. As ocean levels rise, how concerned will the average American politician be with their fate? The Maldives problem is an externality to his or her carbon-burning constituents.

Continuing our present course of neglecting externality costs will insure that we choose a more expensive outcome than the optimal outcome. Today we are ignoring climate change and ocean acidification. We are rolling back pollution regulations to help business. But this will impose much larger costs on society than the savings realized by the businesses. We are rushing into deregulation and renewables without considering the overall cost.

Clearly renewables win over fossil fuels. That's not the question. The question we need to address is which combination of renewables, backup, microgrids, and voltage support wins. And, as we are neglecting externalities, the market cannot correctly decide the correct answer.

The need to account for externalities doesn't mean we should increase regulations across the board. We excel at overlapping regulations. We certainly need to optimize our regulatory system. Just ask your local power plant superintendent how many people inspect the boiler at their plant, to get a good feel for overlapping and unnecessary regulations.

If we continue to neglect externalities, we will go down in history as another in a long line of industries and civilizations who neglected externalities. The same industries and civilizations that failed as they allowed an imperfect market to decide it was not an economically efficient outcome to save them.