Global Electrification Forum

Moderator Philip Moeller is Executive Vice President, Business Operations Group and Regulatory Affairs, at the Edison Electric Institute. David Hutchens is the CEO of Fortis Inc. Laura Sandys is Non-Executive Director for SGN & Energy Systems Catapult. Abigail Anthony is a Commissioner for the Rhode Island Public Utilities Commission.

With the energy grid transitioning into a more decentralized, digitized, and decarbonized system, regulatory models are changing to reflect the evolving role of electric companies. Energy and utilities companies are considering new services and offerings to expand their business models.

Given the changing regulatory and policy landscape, how will these companies of the future operate? How are regulatory models and markets evolving to incorporate new technologies and objectives into the energy system? Panelists at EEI's Fifth Annual Global Electrification Forum, Destination 2050, seek out answers. Enjoy these excerpts.

Moderator and Executive Vice President, Business Operations Group and Regulatory Affairs, Edison Electric Institute, Philip Moeller: We're in a period of great transformation. We are an industry that is the most capital intensive and is a lifeline industry. If people don't have electricity, they might not live.

While we manage this transition from what was a fairly staid industry to one that's evolving dramatically, we not only have to look at new business models, but how those business models evolve. Dave, what's your takeaway of the state of play and what intrigues you in terms of evolving regulatory models?

CEO, Fortis Inc., David Hutchens: It is refreshing to see that the entire world is pointing in the same direction. At the end of the day, everybody is looking at 2050 and saying, net zero by 2050 has to be the goal.

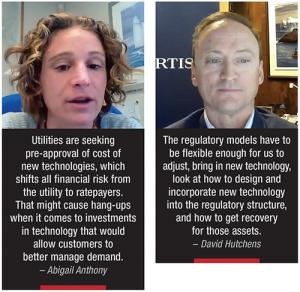

It's early days from a technology standpoint, because the follow-up to that goal is, we don't know how we're going to get there yet. The regulatory models have to be flexible enough for us to adjust, bring in new technology, look at how to design and incorporate new technology into the regulatory structure, and how to get recovery for those assets.

A couple key areas will be the focus of regulation going forward. The first is a stronger focus on performance-based regulation. Outcome focused is common in Canada, but not quite as much in the U.S.

We use it for all kinds of things. Customer metrics, we might use it for nibbling around the edges of environment like energy efficiency standards, what you get measured by and that can go into your PVR structure, but we haven't seen it take root in carbon reductions.

That's going to be key going forward, to have that flexibility so you can to some extent, leave it, mostly, up to the companies, and in the individual jurisdictions to figure out what works best for them and their portfolio in order to reduce greenhouse gases. At the end of the day, that's what it's all about. To start measuring that is important.

The others are some non-standard investments around the edges. Electric vehicle infrastructure is a prime example in Canada and in the U.S. We are the ones who have access to the capital that if you want to build out a transportation, electrification, infrastructure plan, we're the folks to call, because we know how to do that. All that is just an extension of our systems to provide infrastructure for transportation.

The most important concern is the view on the integration of the energy systems. At the end of the day, you have to have the reliability and resilience of your electric grid as you become more dependent on it.

With the electric vehicle conversation, not only are you having things you normally use electricity for, but now you're adding mobility to that equation. The importance of the grid, and the security, resiliency, and reliability are paramount.

We're having particularly in the U.S., a couple of wake-up calls recently, that makes us pay attention to the integration and reliance of one system on another. We need to be focused on, how do those pieces come together, because we're talking about electrifying more of our economy.

If you're not looking at, how do you make that resilient from a fuel supply — and I used fuel loosely, that's renewable natural gas, hydrogen, whatever that might be — you have to make sure you have all of those integrated to provide resilience.

Non-Executive Director, SGN & Energy Systems Catapult, Laura Sandys: We are now moving to fifty million actions and assets, because an EV can do two actions, and we have about thirty-eight million cars in the UK. You can no longer process regulate. You have to, what I would call, perimeter regulate.

That creates rules that you must never ever break, but allow, in many ways, companies to come to the outcome solutions that are carbon outcomes, that are consumer outcomes, and that have cost outcomes. If you think, as a regulator, you're going to be able to, effectively, regulate these fifty million actions and assets, you're going to fall over.

It's the moment of pivot of change. I was Deputy Chair of the Food Standards Agency, and it had the same problem where it was regulating every cafe. It changed its regulatory model to shape around risk and became a risk regulator rather than a process regulator.

That particular dimension is going to be important and changes the focus away from licenses to outcomes and strong penalties as well. I propose we need perimeter regulation, which is based around risk, which is driven and incentivized to outcomes.

Moderator and Executive Vice President, Business Operations Group and Regulatory Affairs, Edison Electric Institute, Philip Moeller: Commissioner Anthony, you have the tough job, now. It might be worth explaining that you have regulatory procedures and guidelines, but you're also subject to state legislation that sets those guidelines for you. That's part of the equation. What are your thoughts?

Commissioner, Rhode Island Public Utilities Commission, Abigail Anthony: Without firm policy, whether that policy comes from your state legislature or federal government, in the absence of firm policy on climate, it's hard for utility regulators to act on climate.

When you do have a firm policy, like in the U.S., most states have renewable portfolio standards, or renewable electricity standards. That makes it easier for the regulator to put the utility in the game but, in the absence of those policies, we can just act around the edges.

We can use tools like performance incentives, and we can adopt an avoided cost in carbon when we're doing a cost benefit analysis. But those are marginal. Here's an example — most new England States, including Rhode Island, are restructured.

We send our distribution utility out to the market to contract for power, or we ask them to contract through bilateral contracts. But our law, at the state level, requires that bilateral contracts between the utility for renewable power have to be better than the market. They have to beat the market.

Without a strong price signal on carbon emanating from either state or federal policy, it's hard for those contracts to beat the power market prices. Regulators can liberally interpret law, but that doesn't get us anywhere near the goals we need in order to address climate change at the most transformative levels.

There isn't a regulatory model that's going to solve climate change. Even if FERC were to pass a carbon tax that is only affecting the power sector, it still doesn't address the transportation sector. In New England, we have a lot of fuel for heating, but it doesn't address other large sources of emissions.

Moderator and Executive Vice President, Business Operations Group and Regulatory Affairs, Edison Electric Institute, Philip Moeller: People will say, regulators need to be bolder, and take more chances, but if things go wrong, the people who were saying that are not going to get the blame, the regulators will.

On newer technologies, and rolling those out to customers as empowering agents of energy consumption, what's your approach? Where's your comfort zone? What can industry do better to help you in those tough decisions when it's risky, and the rewards are there, but there's potential for failure?

Commissioner, Rhode Island Public Utilities Commission, Abigail Anthony: My general orientation toward risk, and I don't know that this changes from topic to topic, its most regulators are approaching risk and it's the foundation of utility regulation to match risk and reward just like investors do. We want to make sure whether it's the utilities or the customers who are going to be exposed to risk that their reward, they might realize investment is commensurate with the risk they're taking on.

One phenomenon I experienced in Rhode Island is, often the distribution company is seeking to shift a lot of the financial risk of new investments onto the customers. They ask for grid modernization proposals, for example, and the utility will not advance a lot of technologies that fall under that grid modernization umbrella without having pre-approval of that investment, or that cost from the regulator.

Pre-approval means the utility is shifting the decision making about whether this is a necessary or prudent investment from themselves to the regulator. In my view, this is what the utilities' job is.

Their job is to make prudent and necessary investments in their distribution system. That's why they have executives, engineers, and power system experts. I don't have that expertise. The most convincing way for utilities to make a business case proposal to regulators is to put some skin in the game first.

What we're seeing is that utilities are seeking pre-approval of cost of new technologies from regulators, which shifts all financial risk from the utility to ratepayers. That might cause hang-ups when it comes to investments in technology that would allow customers to better manage their demand or for the utility to have better visibility and control of the distribution system down to the end user level.

Moderator and Executive Vice President, Business Operations Group and Regulatory Affairs, Edison Electric Institute, Philip Moeller: Laura in the U.K., you've done some forward-thinking, and risky regulation that has evolved from times where people were happy with it, then got less happy, but it was transformational. What are your thoughts on how to empower regulators to take more risk and whether that's necessary?

Non-Executive Director, SGN & Energy Systems, Catapult, Laura Sandys: In some ways, we need to all grow up together. It's not just regulation that's living a little in an old-fashioned world, it's also the sector too.

In the UK, the majority of risk is socialized. If you do not have companies who are properly risk-managing, and are, in many ways, competitive in how they risk-manage, everyone becomes quite sloppy.

All of the cost ends up with the consumer. I've just done something called re-costing energy where we're looking at the system again, and a key plank of this is to ensure that companies own the risks and that they don't just pass it through the system. That's important.

What, in some ways, the regulators need to do is, to understand that the value is moving to the system management aspect rather than the commodity. That changes the nature of regulation, and we'll need to promote flexibility in demand side, but that then requires a whole new range of regulation in consumer protection.

Moderator and Executive Vice President, Business Operations Group and Regulatory Affairs, Edison Electric Institute, Philip Moeller: You do have the advantage of being, essentially, one market. Dave, you're in so many jurisdictions, so many business models where there are different elements of risk. You've got to allocate billions of dollars of investment every year. How do you take this topic and manage it, given the diverse portfolio Fortis has?

CEO, Fortis Inc., David Hutchens: What you posited was a question that says, how do you innovate in a risk-averse environment? That's the situation. Regulators are risk-averse, and utilities are risk-averse. We were brought up in utilities to say, the last thing you can do is take risks, because at the end of the day, we're the most important industry there is.

We are the life-plug of the economy. Nothing works without our electrons, if we circulate around the economy. When you're at that mantle of reliability, resiliency, security, and you're always talking about those things, the idea of taking risks doesn't necessarily come right off the tongue.

That risk balance between whether you socialize it or whether you take it on within a utility or a company, that varies by jurisdiction, by business type, business model, regulatory structure, all of those things.

I would bet that most utilities, particularly now, are looking at ways to, not only grow their own utilities, and I don't mean that from a capital standpoint, or revenue, or profit, I mean, growing it from, how do we serve more of our customers, more of the energy needs on the planet, through clean energy?

When you look at it from that lens, what we need is that balanced risk and return. This is usually where it gets sideways. That's where we, as utilities, might come to a regulator and say, we're willing to take a little of this risk. If it goes well, we keep the money. If it goes bad, we'll basically eat it.

You've got to have the ability to have success when you're taking that risk to tie that risk in return for the things that are above and beyond the risk level you would normally do within your portfolio. If you don't do that, if you can't have that conversation, if you can't figure out how to allocate that risk, you're not going to get anything done.

Moderator and Executive Vice President, Business Operations Group and Regulatory Affairs, Edison Electric Institute, Philip Moeller: Thoughts on how a good, substantive, thorough, and meaningful discussion about how regulation plays as part of worldwide efforts in carbon reduction?

Non-Executive Director, SGN & Energy Systems Catapult, Laura Sandys: In the U.K., our regulator is not responsible for carbon. That is changing and has been passed, the legislation for net zero becomes a national law.

It is driving change a lot. The regulation is going to have to start moving into the users. The industrial sector is driving into heat, where we've got a major problem, because we're all carbon-based heating systems. The regulation is going to have to allow, in many ways, the speed of deployment about innovation, and we need to fail quickly.

There are quite a few pilots at the company. I'm a non-executive director in a gas network and we're putting in some pilots in Scotland for hydrogen into people's homes, green hydrogen. There is a huge opportunity, for smaller companies as well, to innovate and profit from the transition.

I also work on the just transition issue, and it is complicated. In the U.K., you will have to spend money on changing your car and changing your whole heating system. I don't know how many people on this call have got twenty to thirty thousand just sitting around waiting to energy-efficient their home and change their car. The question that has to be asked is, who will pay?

We're going to have to create the mechanisms by which we can allow it, and I would propose it was best to do this through service contracts rather than commodities. We're going to be moving far away from commodity prices, hitting consumers. I can see different business models having to unlock those capital assets.