Moody's Investors Service

Mike Haggarty is Associate Managing Director at Moody's Investors Service and manages ten analysts on their North American Regulated Utility and Power team. He is former lead analyst on Ameren, Entergy, NextEra, and Southern Company.

Swami Venkataraman is Senior Vice President at Moody's Investors Service and manages six analysts on their ESG analytical team. He is former lead analyst on FirstEnergy, NextEra, and PG&E.

Ana Rayes is Assistant Vice President of Moody's Investors Service's ESG team.

Edna Mariñelarena is Assistant Vice President at Moody's Investors Service. She is lead analyst on ALLETE, Atmos Energy, OGE Energy, and Pinnacle West.

Bill Hunter is Associate Managing Director of Moody's Investors Service's Methodology Development Group. He is former lead analyst for AEP, Dominion, and Entergy.

Camila Yochikawa is Associate Lead Analyst-1 at Moody's Investors Service. She is lead analyst on Alabama Municipal Electric Authority, Kansas Power Pool, and Public Power Generation Agency.

Suzanne Wingo is Senior Vice President of Ratings and Process Oversight at Moody's Investors Service. She is former lead analyst for selected corporate finance sectors.

Julie Meyer is Assistant Vice President at Moody's Investors Service. She is lead analyst on Austin Energy and Lower Colorado River Authority.

Nana Hamilton is Vice President-Senior Analyst at Moody's Investors Service. She is lead analyst for AEP, Black Hills, Cleco, Duke Energy, NiSource, and ONE Gas.

Jeff Cassella is Vice President — Senior Credit Officer at Moody's Investors Service. He is lead analyst for Emera, Eversource Energy, NextEra, PG&E, NextEra, and Southern Company.

Jennifer Chang is Vice President — Senior Analyst at Moody's Investors Service. She is Sector lead for public power and lead analyst for CPS San Antonio and NYPA.

Jillian Cardona is an Analyst at Moody's Investors Service. She is lead analyst for El Paso Electric, Evergy, Otter Tail, and Southwest Gas.

Kevin Rose is Vice President — Senior Analyst at Moody's Investors Service. He is G&T Cooperative sector lead and lead analyst on Basin, Oglethorpe, and Tri-State.

Graham Taylor is Vice President — Senior Credit Officer at Moody's Investors Service. He is lead analyst for EMEA utilities and renewable generators, including Abu Dhabi Future Energy, Energia Group, and Israel Electric Corp.

Nati Martel is Vice President — Senior Analyst at Moody's Investors Service and lead analyst for AES, Sempra Energy, WEC Energy, Xcel Energy, and several yieldcos.

Jairo Chung is Vice President — Senior Credit Officer at Moody's Investors Service and lead analyst for FirstEnergy, PPL, and PSEG.

Jim Hempstead is Managing Director for North America Project & Infrastructure Finance at Moody's Investors Service, managing their MIS cyber risk team. He is former lead analyst for AEP, Dominion, Duke Energy, and TXU/EnergyFuture Holdings.

Lesley Ritter is Vice President — Senior Analyst for Moody's Investors Service's Cyber Risk team and former lead analyst on ALLETE, Alliant Energy, Avangrid, and NiSource.

Cintia Nazima is an Analyst at Moody's Investors Service. She is lead analyst for Central Municipal Power Agency/Services and Cooperative Energy.

Everybody knows about credit rating agencies, and how credit ratings reflect the probability of default and expected loss. Moody's Investors Service has been publishing credit ratings on long-lived, capital-intensive assets, such as utilities, pipelines, and other critical infrastructure assets for over one hundred years. Earlier this year, Moody's published an in-depth report that describes how it analyzes and thinks about environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks, and how those risks affect their credit analysis. Although certain aspects of their framework are a bit subjective, their goal is to apply the framework consistently across asset classes, industries, and regulatory regimes.

Moody's began publishing discrete ESG scores in January of 2021, starting with one hundred forty sovereigns. In May, they released almost five hundred additional scores, including over seventy global regulated utilities that own or operate generation assets. Moody's expects to publish next another batch of scores for global utility networks and unregulated power companies, and scores for U.S. public power, Joint Action, and G&T cooperative sectors thereafter.

Moody's is a unique sponsor for this special issue, as their perspective on ESG is different from those of utilities and regulators. We got a chance to (virtually) interview the Moody's team, who are responsible for the coverage of regulated and unregulated utilities, midstream energy, public power, and power project financings, in both the U.S. and in Canada.

What is Moody's up to?

PUF's Steve Mitnick: Good to see you, Mike. It seems like a long time since we hosted that special NARUC lunch. You've been covering electric utilities for a long time and managing this team for a number of years now. How are these new ESG scores different from your credit ratings?

Mike Haggarty: Thanks for the opportunity to contribute to this timely special issue. These new scores provide deeper insight and more transparency into how we think about the credit risks arising from three specific risk considerations — environmental, social and governance. While our ratings tell you about the probability of default and expected loss, which we reflect in our twenty-one-point credit rating scale, we see ESG as three separate and distinct, but often overlapping, components of credit risk. For example, environmental considerations, like carbon transition risk, have been an important credit driver for utilities for as long as I've been covering the sector, and that's saying something.

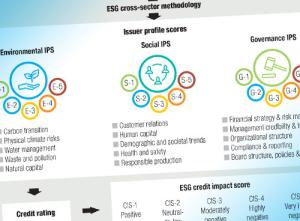

Figure 1 (ESG Integration Into Credit Analysis) and Figure 2 (Our ESG Classification Incorporates Credit Relevant Considerations)

Figure 1 (ESG Integration Into Credit Analysis) and Figure 2 (Our ESG Classification Incorporates Credit Relevant Considerations)

What's different is the language that we now use to articulate those risks to the capital markets. Our new ESG scores include Issuer Profile Scores (IPS). These are our opinions of a utility's exposure to fifteen specific ESG considerations, including significant mitigating factors or strengthening actions that are being taken related to that exposure.

Swami Venkataraman: I'd like to add that once a rating committee determines a rating, say Baa1, we will express how much those specific ESG risks affected the credit rating through our Credit Impact Score (CIS). In other words, our IPS will be used by a rating committee in the analysis to gauge exposure, and once the rating committee assigns a rating, the CIS will convey to the market how much the rating was affected by ESG considerations.

We're not providing an assessment on a utility's ESG performance or its corporate values, rather focusing on scoring from a credit risk perspective. It's really quite distinct from the assessments offered by ESG rating services, such as Vigeo Eiris, a separate company owned by Moody's.

Ana Rayes: And our ESG scores enhance the transparency and consistency of ESG considerations in our credit analysis, which addresses a growing market demand. ESG classification isn't all that precise across financial markets, mostly because of diverse objectives coming from various stakeholders. There's no single set of ESG definitions or metrics that is comprehensive, verifiable, and universally accepted. Moody's defines our view of ESG considerations that are most material to credit quality and then we apply it globally.

Top: Jillian Cardona, Jeff Cassella. Bottom: Jennifer Chang, Jairo Chung.

Top: Jillian Cardona, Jeff Cassella. Bottom: Jennifer Chang, Jairo Chung.

PUF: Has your analytical approach to assessing ESG risks changed?

Edna Mariñelarena: No, our general approach remains the same. We seek to incorporate all material credit considerations, including ESG issues, into ratings. We try to take the most forward-looking perspective that visibility into these risks and related mitigants permits. Our objective is really to capture all considerations that may have a significant impact on credit quality, including ESG risks, and how the fundamental credit strengths of utilities can mitigate those ESG credit impacts.

We haven't seen any changes to outstanding ratings as a result of the updated ESG methodology, although future ratings could be affected by the wider application of this cross-sector methodology. The CIS reflects the impact of ESG considerations on assigned ratings in the context of other credit drivers and is an output of the rating process.

Transparency and governance of the ESG scoring process

Credit Rating Methodologies are the backbone of Moody's credit analysis. Moody's is known for having a comprehensive suite of detailed methodologies that focus on a particular industry sector, and for special asset classes. Regulated Electric and Gas Utilities, U.S. Municipal Utility Revenue Debt, and U.S. Public Power Electric Utilities with Generation Exposure are all examples of sector methodologies. However, their ESG methodology, which is a cross-sector methodology, applies to all sectors globally. It provides a high-level explanation of how ESG factors are considered, where they are not already explicitly described in a sector-specific methodology.

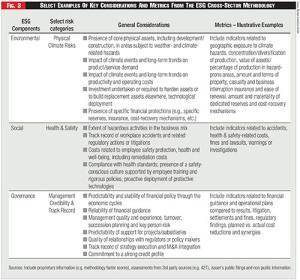

Figure 3 - Select Examples Of Key Considerations And Metrics From The ESG Cross-Sector Methodology

Figure 3 - Select Examples Of Key Considerations And Metrics From The ESG Cross-Sector Methodology

PUF: Transparency seems to be an important buzz word for Moody's. This is a slightly different approach from what many others in the ESG markets are doing. What makes transparency such a focus in your process?

Bill Hunter: We introduced our General Principles for Assessing Environmental, Social and Governance Risks Methodology in early 2019. And then in late 2020, we published a significant update that built on these principles, which introduced the ESG scores just discussed and described, as well as our general framework for assigning these scores. At the same time, we provided a detailed framework for assigning IPS and CIS to sovereigns, followed quickly in 2021 with detailed frameworks for nonfinancial enterprises, and regional and local governments.

So, the methodology updates build on the concepts introduced in 2019 and provide a wealth of insights regarding our approach to analyzing ESG risks and benefits across nonfinancial corporates, project and infrastructure finance, public-sector enterprises, and all levels of governments, including the metrics we may use and the qualitative considerations that are most important in our credit assessment.

We think the IPS and CIS products will provide investors with an enhanced understanding of the credit relevance of ESG exposures because they show, in a very tangible way, how we put the general ESG analytical principles into action for a specific issuer or transaction.

Top: Nana Hamilton, Bill Hunter. Bottom: Edna Marinelarena, Nati Martel.

Top: Nana Hamilton, Bill Hunter. Bottom: Edna Marinelarena, Nati Martel.

Along with our plan to establish IPS and CIS for more sectors, we recently completed a request for comment proposing a detailed ESG framework for financial institutions. Like all our methodologies, our ESG cross-sector methodology is publicly available on moodys.com.

Camila Yochikawa: We should also note that the most recent update to the ESG cross-sector methodology has three parts. It covers sovereigns, enterprises, and regional and local governments. We include public power utilities and other critical municipal infrastructure under the enterprises part of the methodology, in addition to investor-owned utilities and privately managed infrastructure.

PUF: How does the new ESG cross-sector methodology relate to your other rating methodologies?

Suzanne Wingo: We have over two hundred rating methodologies that cover most sectors and many financing structures. And we rate companies in industries that have greater downside credit exposure with regard to environmental risk, like mining, and governments that have more prominent social risks. Our Ratings Process and Oversight team collaborates with rating groups to implement standard processes that support analytical rigor and consistency in applying our methodologies.

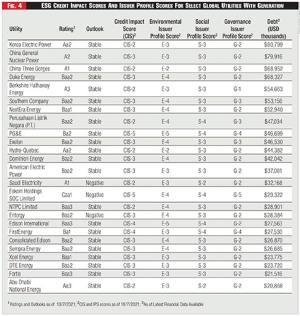

Figure 4 - ESG Credit Impact Scores And Issuer Profile Scores For Select Global Utilities With Generation

Figure 4 - ESG Credit Impact Scores And Issuer Profile Scores For Select Global Utilities With Generation

As the group credit officer for the global Project and Infrastructure Finance Group, I provide a broad perspective that helps promote consistency of scoring both within the infrastructure portfolio and across sectors. Typically, the rating teams score a small group of benchmark issuers in each sector first, followed by the rest of the sector. On certain occasions, the peer consistency checks provide feedback that allows analytical teams to align their approaches a little bit better.

PUF: Can someone explain how this works? What kind of data do you focus on and what do you think of disclosure practices?

Julie Meyer: So, the types of data and metrics we use are described in the methodology and are tailored to each sector. The challenge with global data is that it's difficult to identify data and metrics that are both relevant to credit risk and measured or reported consistently around the world. Our ESG approach includes both quantitative data and qualitative considerations, and the latter are especially important in a world without consistent disclosure standards.

We use public disclosures and our in-house assessments like the Moody's Carbon Transition Assessments, and we also look at other data and information from Moody's affiliates and relevant third-party sources, such as the Edison Electric Institute's ESG disclosure framework. Also, we incorporate nonpublic information that many issuers share with us, like information that we obtain as part of the credit rating process.

Top: Julie Meyer, Cintia Nazima. Bottom: Ana Rayes, Kevin Rose.

Top: Julie Meyer, Cintia Nazima. Bottom: Ana Rayes, Kevin Rose.

Nana Hamilton: We certainly support improved disclosure on ESG issues, but we don't require companies to disclose anything specific. We see regional differences and acknowledge that disclosure on ESG matters may vary because of differences in reporting standards across jurisdictions as well as different levels of market focus on certain ESG topics. Where we do have information, we look at how these exposures may be similar across a sector or whether they vary widely within that sector.

PUF: What kind of time horizon do you incorporate in this analysis?

Swami Venkataraman: Well, our credit analysis doesn't look over a specific time horizon. It's intended to incorporate relevant credit considerations as far into the future as visibility permits. For the climate risk assessment frameworks, we strike a balance between the need to assess a prolonged period during which the effects of climate change can crystallize and the reduced visibility into the impact on a particular issuer of extremely long time horizons. But in thinking about long horizons, it's also useful to remember that credit ratings are opinions of relative credit risk.

The expected time horizon of the E, S, or G exposure may mute the effect on the rating, and many enterprises have meaningful exposure to risks that are expected to become material over a relatively long timeframe. Even so, in these cases, an enterprise may have sufficient time and financial strength to adapt as needed to meet its ESG challenges.

Figure 5 (Environmental Categories And Scores For Select Utilities And Municipalities) and Figure 6 (Cyber Vulnerabilities In Key Infrastructure Sectors)

Figure 5 (Environmental Categories And Scores For Select Utilities And Municipalities) and Figure 6 (Cyber Vulnerabilities In Key Infrastructure Sectors)

Ana Rayes: For physical climate risks, we use a single scenario and primarily focus on the implications for the next thirty years. The physical effects of climate change are largely locked in through 2050 because of the continued impact of historical emissions. It's not until about midcentury that we expect there to be a meaningful divergence in long-term global temperature changes and other physical hazards under different emissions scenarios, commonly referred to as representative concentration pathways (RCPs).

In light of historical emissions patterns and to account for the risk of tipping points and feedback loops, we base our analysis of physical climate risks to 2050 on RCP 8.5, a high-emissions scenario.

Applying the ESG framework

One of the most rigorous parts of ESG scoring is global consistency — and Moody's is great at making sure that utilities in the U.S. are being held to the same standards as utilities in Canada! For each specific consideration, say environmental risks associated with waste and pollution, Moody's analysts think about a common set of things that are relevant to credit. Things like fines, penalties, regulatory intervention, and other costs triggered by pollution incidents, including coal ash. For utilities responsible for nuclear waste storage, they look at remediating contaminated plant sites or expected costs to meet more stringent environmental mandates.

PUF: Is there a way to summarize the main findings of the ESG scores with regard to utilities?

Top: Swami Venkataraman. Bottom: Suzanne Wingo, Camila Yochikawa.

Top: Swami Venkataraman. Bottom: Suzanne Wingo, Camila Yochikawa.

Jeff Cassella: For global utilities with generation, ESG issues generally have a moderately negative credit impact.

In terms of environmental risks, the main issues for utilities with generation are related to carbon transition and physical climate risks. And for carbon transition, existing assets could become uncompetitive in the face of growing renewable penetration, higher carbon costs, or restrictions on operating carbon-intensive plants.

We also look at several key aspects of physical climate risk, including physical damage to assets given the increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events, the risk that extreme temperatures will expose generators to volatile commodity prices, and the risk of drought to hydro plants and nuclear plants that rely on water cooling.

In most of the U.S., utilities can recover many of these costs under normal circumstances, but existing regulatory mechanisms may become strained if costs of carbon transition and managing more extreme weather rise significantly.

And that brings us to social risks, which we also see as moderately negative for most of the sector, largely because of demographic and societal trends. Electric utilities are really at the heart of major societal trends, such as decarbonizing generation and electrifying transportation and heating. Utilities will be under great pressure to facilitate these trends while maintaining reliable and affordable electricity for households and businesses. The focus on ensuring reliable and affordable service, upholding safety standards related to nuclear power, waste disposal, and natural disasters, and meeting customer demands for clean energy can influence regulatory actions if not executed properly.

On the other hand, governance considerations generally don't pose a major risk for most companies in the sector, at least in the US. Governance risk tends to be issuer-specific, and management practices and policies can either mitigate or exacerbate environmental and social risks.

PUF: How do you see ESG risks for public power utilities?

Jennifer Chang: Social risk has always been important for public-sector utilities because their shareholders are also their customers. Public-sector utilities' revenue collection doesn't include profits, or taxes, and these utilities tend to have rate-setting authority to collect revenue when they need to — we look at both their ability to raise rates, as well as their willingness. We have been looking for a long time at how these utilities provide access to basic services like electricity, water, and gas for heating and cooking within their communities.

Environmental risk and carbon transition are a very important topic for public power utilities, particularly for smaller utilities that may still be heavily reliant on fossil fuel-based generation, or utilities in certain parts of the country that don't have strong economic bases. But again, their ownership by state and local governments is often a bigger driver of the credit rating.

PUF: How do you think about stranded asset risk?

Jillian Cardona: Although the sector has a lot of stranded asset exposure, it doesn't have a lot of stranded asset risk because U.S. regulators have a strong track record of allowing utilities to recover from their customers the cost of stranded assets. Our carbon transition scores are a good, near-term example about how we see potential shifts in scores as the sector works toward decarbonization.

We think carbon transition risks will decline for utilities with generation over the coming years, given the number of net-zero pledges and the ongoing investments in renewable energy. The average global utility IPS for carbon transition is a "3," which signifies a slightly negative risk exposure over time, even with the roughly four hundred billion dollars of U.S. assets that are potentially exposed to increasingly stringent carbon emissions, assuming twenty-five percent exposure against $1.6 trillion of total assets.

PUF: It's not all environmental, so then how do you look at social risks?

Kevin Rose: So, for social risks in our sector, a lot of it is related to demographic and societal trends. We factor in the risks of adverse legislation, political intervention, or customer losses because of ESG considerations. And we do consider unusually strong or weak demand growth, or the threat of restricted access to capital because of lender ESG exclusions.

My favorite consideration is management credibility and track record, one of the key governance risk factors, where we discuss the predictability and stability of a company's financial guidance through the cycle, any evidence of commitment to the rating and the quality of regulatory or policymaker relationships.

Graham Taylor: We do differentiate between electric and gas networks with respect to the time horizon and threat of stranded assets. Almost all regulated utilities with generation were scored at least 3-Moderate for carbon transition and the physical impacts of climate change risks, although this also reflects commodity hedging risks.

We also see how purely underground/undersea networks are safer from flooding and sea level rise and we understand how huge geographic diversification can mitigate high physical risk in our Four Twenty Seven, Inc. data.

But we are taking a slightly harsher view on gas networks, especially if there are plans — or talks of plans — to phase out gas by a certain date. Still, regulatory or legislative mandates that have future targets and no real teeth or consequences don't usually amount to any meaningful credit impact.

PUF: Are you looking at new technologies, like hydrogen, in the context of ESG?

Jennifer Chang: We are watching closely the potential growth of the share of hydrogen as a fuel in the economy not only related to the power sector, but also to transportation, industry, and other sectors.

And hydrogen today is practically nonexistent in power generation, and it certainly has some hurdles to work through, like high costs and the infrastructure refurbishment needed to accommodate it. However, it does have significant potential in helping decarbonize the grid by 2035. There are several utilities with pilot projects underway, including Dominion and Sempra, as well as NextEra.

In the public power space, we are aware of many pilot projects outside of the Intermountain Power Agency in Utah, which is working on a well-known large gas-fired power plant that will be able to use up to thirty percent hydrogen by 2025 once it begins commercial operations.

Nati Martel: Carbon capture sequestration is another alternative that some generators may consider to achieve needed GHG emission reductions in the long run. Even though high costs and lack of widespread commercial use are still deterrents, there are some carbon capture and storage projects under consideration that intend to make use of expanded tax credits. This may be another route that some generators choose to take as they evaluate options for their carbon transition plans, and also as technology costs come down.

What are the next steps?

PUF: Is there a key takeaway for utilities and your ESG efforts?

Jairo Chung: From a credit perspective, we think utilities are well positioned to benefit from the global priorities around ESG and the efforts to decarbonize the planet. We view utilities as critical infrastructure assets, and our own default studies show that the ten-year cumulative average default rate for all rated corporate infrastructure and project finance securities is about one sixth of all rated nonfinancial corporates.

Utilities continue to invest heavily into their rate base to a huge wave of capital investment to decarbonize and make the grid more intelligent, communicative, and resilient. No other sector can reduce GHG emissions as quickly, and as permanently, as power generation while at the same time supporting other sectors' decarbonization goals. As regulated critical infrastructure businesses, utilities also tend to have reasonably good governance practices compared with nonfinancial corporates.

PUF: How do you think state utility regulators will use these ESG scores?

Mike Haggarty: Notwithstanding how much we appreciate the stability and predictability of most regulatory proceedings, I've been around this business long enough to know better than to speculate on how fifty state regulatory bodies might use our new ESG scoring framework. But I do know that most regulators want to understand how complicated risks — like ESG — can have an impact on asset classes and across their regions of interest.

For example, I wouldn't be surprised if we see regulators focus on the scores of their respective states or cities, in addition to those of the utilities they oversee. In the future, as we roll out scores across a wider set of companies, they will also see our framework being applied consistently to other infrastructure assets or business. I am thinking toll roads, airports, seaports, and other major industries. State utility regulators will have better insight into how we see these specifically defined risks impacting a utility, and this might enrich rate case proceedings.

PUF: So, what's next?

Jim Hempstead: It is hard to tell for sure, but we are focusing a lot of energy on assessing cyber risk. We recently announced a significant investment in a company called BitSight, which is a global leader in cyber risk security ratings. We are stepping toward our effort to incorporate cyber risk into credit analysis in a consistent and transparent fashion.

This will take time, given the complexity around how wide-spread cyber risk can impact an organization. We still see cyber risk as an enterprise-wide risk, which means the risk will ultimately reside at the board of director level, or at the level of the Trustee or other public power governance structure. Regulators, including the like of the SEC, can influence the pace and urgency of cyber risk mitigation efforts.

Lesley Ritter: Cyber risk is not new to the infrastructure sector. In fact, we have been writing about and considering cyber risk in our credit analysis for nearly a decade now. What has changed is the frequency, scale, and impact of cyber events on critical infrastructure. The headline-grabbing ransomware attack on Colonial Pipeline earlier this year made that abundantly clear.

The attack, which directly affected the IT side of Colonial's business, ended up taking the pipeline offline for nearly a week, and caused fuel shortages up and down the eastern seaboard. We are not aware of any U.S. utilities experiencing a Colonial-type event. But we are seeing successful cyberattacks on utilities in other regions, such as Enel, EdP and Eletrobras.

Cintia Nazima: Cyber risk is rising at a faster clip than we previously thought, and it is emerging in more complex and novel ways. We also see more regulatory oversight and a shifting cyber insurance market, likely because cyber risk is consistently being identified as a top enterprise risk.

But, disclosure needs to be improved. The potential exploitable attack surface and ensuing business disruption risks grow as utilities and pipelines keep digitizing their businesses and processes and becoming increasingly interconnected. Add to that an evolving attacker landscape that now includes financially motivated actors and nation states, and you have created a very potent mix that heightens the sector's overall cyber risk.