Positioning to win in the contest for scale.

Jack Azagury (jack.azagury@accenture.com) is Accenture’s North American Management Consulting lead for the resources industries, and Walt Shill (walt.shill@accenture.com) is global senior director at the company. Ted Walker (ted.h.walker@accenture.com) is a senior manager in the Accenture Utilities Strategy group. The authors acknowledge contributions from Jan Vrins, Accenture Utilities Management Consulting group, and Jason Allen, Accenture Research.

In the last decade, the utilities industry has behaved more like the tortoise than the hare in the race to consolidate. While companies in sectors such as telecommunications, banking and oil have actively joined forces and reshaped their industries, utilities have followed a conservative route toward mergers and acquisitions (M&A). Recent trends indicate that utilities are no longer idling on the starting line—in the past 18 months alone we have seen a greater growth in the concentration of the top players in the industry than in the preceding 10 years.

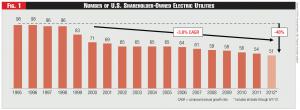

Now, the forces for continued fragmentation are being overshadowed. Even the stringent regulatory environment can’t compete with decreased avenues for earnings growth, increasing demands for capital expenditures, declining returns on equity, and other factors that are accelerating the pressure to consolidate. In the last 10 years, the number of investor-owned electric utility holding companies in the United States has declined from 69 to 51, a trend we expect to accelerate, leading to less than 40 U.S. investor-owned electric utility holding companies by 2020. Some companies are better positioned than others to drive consolidation—and some need to reevaluate their strategy based on their positioning if their ambitions are to grow through M&A. So how can utilities industry players better prepare themselves for the race to consolidate?

Evolving from the 19th century, the utilities sector is one of the most established industries. Yet for many years, competition was far from encouraged. Then, in 2005 Congress lifted the regulatory constraints of the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935. A number of other market and economic forces also came into play, putting utilities on track for more consolidation. Indeed, the U.S. utility sector experienced a spike in M&A announcements in 2011 that exceeded the total value for all deals in the previous three years.

Accenture has evaluated the key players according to their readiness to lead consolidation through a successful merger and acquisition strategy, analyzing 50 electric and electric-gas combination utilities. This analysis suggests the industry has now turned the corner on the drive to consolidation—and many companies are surprisingly unprepared.

The Case for Consolidation

Several escalating forces will drive the pace of consolidation. They include: increasing capital investment requirements driven by regulations and replacements; reduced opportunities for earnings-per-share growth due to tougher rate cases and declining allowed returns on equity (ROE) in a challenging economic environment; the need to achieve operational savings to exploit untapped value; and fear of the unknown and the potential for unforeseen events—such as the effect of the devastating Japanese earthquake and tsunami, which caused a nuclear accident at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant in March 2011.

These forces will continue to face headwinds from several factors that will moderate the overall pace for consolidation. Moderating factors include: regulatory push-back (“what’s in it for the customer or state?”); the fragmented gauntlet of regulatory approvals; a rising forward price-to-earnings ratio; and disappointing merger integration results in the past.

In balance, the forces driving consolidation likely will continue to prevail. While the pace of consolidation will continue to trail that of other industries, it will be sustained and greater than it has been in the past. The number of shareholder-owned electric utility holding companies has declined by 48 percent since 1995 (see Figure 1). If this trend continues at a similar or faster rate as expected, by 2020 the number would decline to approximately 40 companies or less.

While most mergers in the U.S. utilities industry on average haven’t delivered shareholder value, high-performing companies with lower cost structures have delivered superior shareholder value through M&A—by a factor of two to three—and we expect this trend to continue. Further, future deals likely will rely more heavily on deeper operational synergies, rather than seeking out only the more obvious balance sheet improvements, reduced hedging costs, and corporate back-office consolidation.

In addition to the absolute number of utilities decreasing, there has been a significant increase in the concentration of the largest utilities. For most of the past 12 years, major M&A activities were very limited among the top 10 largest utilities—with virtually no mergers among them until recently. In 2011 and 2012, we saw a departure from this trend, driven primarily by the Exelon-Constellation and Duke-Progress mergers. These changes in concentration within the industry, particularly among the larger players, support the hypothesis that a new pattern of more active mergers and acquisitions is emerging.

History is littered with examples of industry leaders who have failed to adapt to changing times and suffered the consequences. Times are changing for the U.S. utilities industry. While previous M&A activities were largely concentrated on the smaller players, future M&A activity likely will involve more mid-sized and larger utilities. We have already seen this trend over the last 10 years—the average deal size over the last five years was nearly 50 percent larger than that in the previous five-year period. This will be due in part to the level of prior consolidation—that is, the average investor-owned utility, or IOU, today is nearly twice the size of the average IOU 15 years ago—and in part as a result of industry forces favoring larger players.

The Future Consolidators

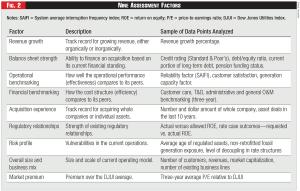

Accenture’s analysis used nine factors that combined publicly available data and knowledge of the industry to explore how companies are positioned to drive consolidation in the U.S. utilities sector (see Figure 2). The research identified three broad categories of companies with respect to their positioning for M&A activity. Their characteristics are as follows:

n Green Flag: Companies that are better positioned to lead the consolidation race are relatively strong financially, are likely to have a growth track record, and maintain high-performing operations.

n Yellow Flag: Companies that have strength in multiple areas—such as balance sheet, operational performance, acquisition experience, or overall size and scale—while also having several factors that prepare them less well for consolidation, likely will pursue smaller acquisitions or mergers of equals with peers in the same category.

n Red Flag: Companies that have strengths in one or two areas, but have multiple factors that make it more difficult to acquire others and more likely that they will be acquired, may continue to operate successfully as independent companies, or will fetch strong premiums when acquired.

Green flag companies are those with a larger overall size, have a track record of growth by acquisition, and show a strong financial performance and standing. A strong balance sheet is one of the most important characteristics of this group. Given that size is a key consideration in the analysis, unsurprisingly, most of the green flag companies are large, as measured in revenue (greater than $10 billion) and market capitalization (greater than $20 billion). Yet not all large companies qualify for a green flag. In addition, nearly half of the small companies on the list—by market capitalization—are in the yellow flag category (see Figure 3).

While utilities are quite different from other industries, there are lessons to be learned from companies that have undergone consolidation in other sectors. For instance, as cautious players discovered in the recent telecommunications industry consolidation, those that wait on the sidelines during periods of active consolidation might regret their hesitation once the market leaders have had first choice of the best combinations the market has to offer. In an extreme example, two companies from the telecommunications industry were somewhat forced to merge—despite their lack of operational, customer, and technology compatibility—once the consolidation played out and other options for acquisitions were no longer available.

Looking back, the positioning of four companies in two recent mergers illustrates two models that likely will be common in future industry mergers. Green flag companies will be actively pursuing companies in the two other categories in the coming years. Similarly, recent merger activity between two yellow flag companies suggests that mergers of equals will be a common model in the future (See Figure 6).

Moving into the Fast Lane

Understanding its current positioning in the marketplace to seize potential growth is helpful for any utilities company, but it’s important to recognize that the outcome remains uncertain. Being ahead of the rest is beneficial, but it’s certainly no guarantee of being the first past the post. Similarly, companies that might find themselves ranked in a yellow or red flag category shouldn’t feel they’re unable to consolidate—it simply means there’s a need to drive harder to overcome any initial positioning weaknesses. (See “Performance Improvement through M&A,” and “M&A Drivers.”) As we have seen in the market in recent years, several companies that were relatively small 15 years ago—and likely ranked in the yellow or red flag categories—have repositioned themselves. Through a series of transactions and greater positioning strength, these same companies now find themselves ranked among the strongest companies Accenture analyzed.

Of course, setting off to consolidate immediately might not be the preferred route for many companies. But leadership teams and board members shouldn’t only proactively assess their best-fit options—which most utilities already are doing on an ongoing basis—but more importantly should assess and develop their readiness for mergers and acquisitions (see Figure 5).

Green flag companies can improve their positions by leveraging their existing strengths and fully preparing for acquisitions by actively nurturing their best-fit combinations—those that are likely to create the most value. They also should be developing their own capabilities, along with strategic process and technology investments, to derive current operational benefits and realize future benefits in forthcoming acquisitions. For instance, this might be as simple as creating a customized playbook with 100-day plans, or as complex as establishing a dedicated post-merger integration team, with standardized integration processes. Green flag utilities also should fully integrate and harmonize their operations from prior acquisitions. Finally, green flag utilities should prioritize their investments in processes and technologies that have the clearest links to eliminating any untapped value in operations. Examples of this include a flexible shared services function; a standardized yet scalable set of processes, procedures, and policies; and an IT roadmap that supports M&A.

Yellow flag companies, in addition to the above steps, can raise their game by focusing on the areas that will strengthen them in relation to their peers. This means taking a good, honest look at their operations and focusing on improving low- or mid-performing functions. Yellow flag utilities should identify their desired positioning in the context of whether they see themselves as acquirers or the acquired—or whether standing alone is the best path for their stakeholders. In addition, they should explore mergers of equals with similar-sized utilities. They should understand which companies might view them as potential targets and proactively develop their response. Likewise, they should monitor their possible partners for changes that make them more attractive, or might accelerate timing. Yellow flag utilities also should make targeted strategic investments in processes and technologies where the payback on current operations is clear.

Finally, companies in the red flag group should drive a change in their positions and performance through operational improvements and by strengthening their balance sheets; such improvements will serve them well under any circumstances. They must attend to any high-risk areas that might cause unexpected frailty or diminish their attractiveness. They need to develop their own view of which companies would be the most attracted to acquire them and proactively open discussions; it’s far better to select potential acquirers and evaluate the options themselves than to have a combination unexpectedly forced upon them. In addition, red flag utilities should maximize the flexibility and decision-making power of current management by keeping change-of-control constructs in line with industry standards. Above all, the accent should be on living within their means; long-term capital spending plans must be aligned with capital availability.

Despite the unpredictability of the markets, planning and preparation are the bywords for the future of utilities. Creating a multi-year roadmap is the starting point to achieve operational synergies—augmenting the 100-day post-merger integration plan with a 1,000-day operational integration plan. Most post-merger integration is measured in days, and experience shows that many merging utilities first undertake superficial integration steps and postpone the more complex—and more valuable—operational integration to many years later, if it ever happens at all. For example, the 100-day post-merger integration activities often mean rationalizing headcount from a top-down perspective, while 1,000-day operational integration activities involve looking deeper at processes, integration, and technology to help optimize the efficiency of a particular function. As illustrated by leading consolidators in other industries, those that organize and manage integration as a core competency, invest in infrastructure, and boost capabilities are able to accelerate value creation.

Where Next?

In an evolving market, the emphasis is on agility and being able to adapt to capitalize on opportunities and stay ahead of the rest. Those companies that achieve better and more consistent outcomes—i.e., shareholder value and merger value realization—not only manage the risk of volatility, but also take advantage of uncertain times to improve their competitive edge. Similarly, fully understanding a utility’s positioning for consolidation—and acting on it—can provide a meaningful advantage.

Clearly, mergers and acquisitions aren’t easy. Dramatic changes in political, regulatory, and economic landscapes are adding further complexities to difficult transactions. But the results can be rewarding. In particular, the potential for operational excellence as an outcome for M&A activity is high. For the acquired, if they’ve embraced operational excellence they’re more likely to command a premium; for the acquirer, drawing operational excellence into the organization through consolidation is a prime path to realizing value. Indeed, as analysis has shown, wherever utilities companies are ranked in readiness for M&A activity, those achieving high performance are more likely to gain higher synergy outcomes. As such, companies would do well to perform every day as they do on their best day, if they aim to reach the checkered flag in the race to consolidate.

Endnotes:

1. Includes publicly traded electric utility holding companies, as defined in EEI 2010 Financial Review.