The Deutsche Bank case and the meaning of ‘price manipulation.’

Bruce W. Radford is publisher of Public Utilities Fortnightly.

A few months back, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission directed Deutsche Bank Energy Trading LLC to show cause why it shouldn’t be assessed a civil penalty of $1.5 million and be made to return some $123,000 in allegedly unjust profits from power trading in markets run by the California ISO.

FERC acted on an investigation and proposed findings reported by its internal Office of Enforcement. That investigation had found evidence that Deutsche Bank engaged in a “fraudulent scheme” of trading in one market to benefit a position in another, aided by “falsely designating” certain imports and exports as complying with ISO rules.

Moreover, FERC’s enforcement staff alleged that Deutsche Bank had “conceived and executed” a program of trading in spot energy markets, from January through March 2010, so as to benefit certain complementary positions that Deutsche Bank had held on CRRs—“congestion revenue rights,” the term used by the ISO in California to describe what are more commonly known, in East Coast markets, as FTRs, or “financial transmission rights.” (See, Order to Show Cause and Notice of Proposed Penalty, Dkt. IN12-4, Sept. 5, 2012, 140 FERC ¶61,178.)

In purely dollar terms, the Deutsche Bank case falls short of some other recent enforcement actions. It was only this past March that FERC exacted a $245 million settlement from Constellation Energy Commodities Group—the largest ever ordered by the commission, including penalty and disgorged profits.

Yet this comparison wasn’t lost on John Estes and the rest of Deutsche Bank’s legal defense team from Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom. Their response to the charges from the FERC staff, filed early last month, acknowledges the small sums involved:

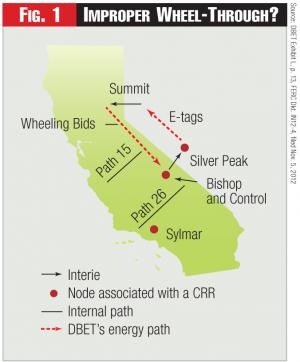

Figure 1 - Improper Wheel-Through? In referring the Deutsche Bank matter to FERC for possible enforcement action, the California ISO’s department of market monitoring found that DBET traders had established a pattern of circular trading, by purchasing power exports out of CAISO at the Silver Peak intertie node, moving them across Sierra Pacific Power transmission to the Summit node (the E-Tag dotted line), and re-importing the same power back into CAISO, to be wheeled back to the starting point, in a manner “inconsistent with ISO and FERC market rules.” However, the Deutsche Bank defense team claims that no circular trading occurred, as evidenced by the lack of E-Tags for any alleged wheeling within CAISO from Summit to Silver Peak. Source: DBET Exhibit L, p. 13, FERC Dkt. IN12-4, filed Nov. 5, 2012.

Figure 1 - Improper Wheel-Through? In referring the Deutsche Bank matter to FERC for possible enforcement action, the California ISO’s department of market monitoring found that DBET traders had established a pattern of circular trading, by purchasing power exports out of CAISO at the Silver Peak intertie node, moving them across Sierra Pacific Power transmission to the Summit node (the E-Tag dotted line), and re-importing the same power back into CAISO, to be wheeled back to the starting point, in a manner “inconsistent with ISO and FERC market rules.” However, the Deutsche Bank defense team claims that no circular trading occurred, as evidenced by the lack of E-Tags for any alleged wheeling within CAISO from Summit to Silver Peak. Source: DBET Exhibit L, p. 13, FERC Dkt. IN12-4, filed Nov. 5, 2012.

“Given that Enforcement seeks sanctions here of only $1.6 million—a small amount compared to other alleged energy manipulation cases—one might wonder,” the defense writes, “why DBET has not already settled.”

“After all, the cost of defending the case is likely to exceed the amount Enforcement seeks.”

Yet the stakes couldn’t be higher. And the reason, says the Deutsche Bank defense team, comes down to a “point of principle.”

Recall that in the Constellation settlement, enforcement staff had found CECG culpable of trading in one set of markets (virtual and day-ahead physical schedules) with the aim of maximizing returns in others (financial positions on contracts for differences). And now, in the Deutsche Bank matter, staff advances a similar-sounding charge: that Deutsche Bank “falsely scheduled unprofitable physical exports at the Silver Peak intertie with the intent to benefit its financial positions [on congestion rights] in the ISO system. (See, 2012 Report on Enforcement, FERC Office of Enforcement, Dkt. AD07-13-005, Nov. 15, 2012, p. 7.)

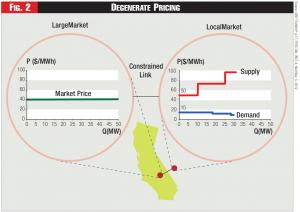

Figure 2 - Degenerate Pricing - This figure depicts a hypothetical combination of supply and demand bids that could’ve created a situation of “degeneracy” at the Silver Peak intertie node, by which the market-efficient, security-constrained, least-cost dispatch solution under the California ISO market tariff could’ve indicated not a single, unique market-clearing locational marginal price (LMP), but a range of prices, falling between the lowest-priced supply bid (import bid) and the highest-priced demand bid (export bid)—any one of which would be viewed by the ISO software as a “correct” price. The Deutsche Bank defense team argues that the California ISO’s market software improperly selected a default price from within the degenerate range that violated the ISO’s tariff, which defines the LMP price as the value of serving the next increment of demand.

Figure 2 - Degenerate Pricing - This figure depicts a hypothetical combination of supply and demand bids that could’ve created a situation of “degeneracy” at the Silver Peak intertie node, by which the market-efficient, security-constrained, least-cost dispatch solution under the California ISO market tariff could’ve indicated not a single, unique market-clearing locational marginal price (LMP), but a range of prices, falling between the lowest-priced supply bid (import bid) and the highest-priced demand bid (export bid)—any one of which would be viewed by the ISO software as a “correct” price. The Deutsche Bank defense team argues that the California ISO’s market software improperly selected a default price from within the degenerate range that violated the ISO’s tariff, which defines the LMP price as the value of serving the next increment of demand.

But at the same time, the legal defense team from Skadden Arps appears to have made at least a prima facie case that Deutsche Bank’s scheduling of physical transactions wasn’t false or misleading, nor intentionally unprofitable. If this defense should hold up—that Deutsche Bank traded honestly, openly, and efficiently (with a profit-seeking intent)—then FERC’s case will be left resting solely on the notion that market manipulation can be shown simply through trading in one sphere, such as physical schedules in a spot cash market, while holding a complementary position in another, such as a financial market that trades hedging derivatives.

Deutsche Bank and its Skadden Arps legal team reject that notion as inimical to markets. In fact, they’ve come to see themselves as going to bat for an “entire industry”—as defending the very idea of wholesale power trading, as practices in markets run by FERC-sanctioned (ISO-RTO) regional grid operators:

“The legal position Enforcement has taken here is radical,” writes the Deutsche Bank legal defense team from Skadden Arps. “Essentially,” they assert, “Enforcement’s position is that knowingly trading in two related markets is per se unlawful market manipulation, even if the trading is profit-seeking in both markets.” (See, Answer of DB Energy Trading to Order to Show Cause, Dkt. IN12-4, p. 1, filed Nov. 5, 2012.)

And on this point the defense has brought out the big guns. Testifying on behalf of Deutsche Bank, the electric industry expert and Harvard Prof. William Hogan sees the case as a threat against the market regime he helped create and continues to stand for:

“If holding a financial contract that benefits from the price impact of a physical transaction were to be deemed all that is required to establish price manipulation, then the entire foundation of efficient electricity market design would be destroyed with one stroke.” (DBET Exhibit P, Affidavit of William W. Hogan, p. 36.)

Also testifying for Deutsche Bank is consultant Roy Shanker, who argues that such a theory, if accepted by FERC, will bring chaos to wholesale power trading:

“How do you make any decisions regarding manipulation,” he asks, “when it is indistinguishable from rational economic behavior.” (DBET Exhibit O, Affidavit of Roy J. Shanker, p. 84.)

Are Hogan and Shanker crying wolf?

Well, maybe a little, but now here comes the really interesting part—the real villain in this case might not be the traders, but the software.

It turns out that RTO/ISO markets have a weak spot at thinly traded export nodes that intertie with adjacent non-market areas. A phenomenon known as “degeneracy” can develop, according to Hogan and Shanker, whereby the software algorithm that solves the efficient, least-cost dispatch can’t resolve a single market-clearing locational marginal price (LMP) at the node in question.

Normally the software will first determine a simultaneous clearing of all supply and demand bids to arrive at a single, least-cost dispatch of resources that obeys all security constraints. But then will discover—to the dismay of its silicon brain—that this dispatch occurs not just at a single, unique market price, but can be solved mathematically across a range of multiple alternative LMPs, each of which the software will see as a correct, market-efficient price.

This range of prices can be volatile, according to Hogan and Shanker, leaving traders balanced on a knife-edge. That’s because a single, small incremental bid can instantly collapse the pricing range at such a thinly traded node and produce a new, much higher or lower LMP, putting the trader out of the money.

The defense team argues that this degeneracy phenomenon occurred in the Deutsche Bank case, causing the California ISO software to send potentially misleading signals to Deutsche Bank traders concerning prices and congestion. In fact, the defense team analyzed the prices and congestion that the ISO software posted, with the assistance of the ISO’s Department of Market Monitoring, and drew a remarkable conclusion. The defense found, it claims, that the ISO must have pre-programmed its software with an arbitrary “default” solution. This default, the defense says, would always resolve the price ambiguity by selecting one price out of the degenerate range of all possible correct prices, and posting that one price as the LMP, and thus the indicator of the direction and value of congestion.

Moreover, according to the defense (see DBET Answer, p. 53), this default price violated the ISO’s filed tariff and misled the Deutsche Bank traders:

“Whenever the software selected the low end of the degenerate range, the resulting low price … created an apparent profit opportunity for market participants.”

Silver Peak to Summit

To understand what happened, turn to Figure 1. DBET claims its traders sought profits in moving power from the Silver Peak intertie node to Summit, as the historical market data seemed to indicate an average price differential (higher at Summit, lower at Silver) of about $10 to $14/MWh, whereas the necessary transmission service to be obtained from Sierra Pacific Power was thought to cost only about $5 to $6, with CAISO charges running only about $1.50 to $2 to submit export bids at Silver Peak (bidding to buy power exported there from the ISO), and import bids at Summit (to sell back into CAISO).

But as Deutsche traders planned to submit mainly self-scheduled (price-taker) export bids at Silver Peak, they first chose to hedge price risk (the risk that the buy price at Silver Peak might rise too high) by acquiring CRRs at auction that would pay off if congestion appeared in the export direction—i.e., if prices at the Silver Peak intertie exceeded prices inside CAISO.

DBET in fact scheduled and reported these physical transactions, with trading volumes varying from day to day, from January through March 2010, as indicated in Figure 1 by the dotted line labeled “E-Tags.” And as DBET wanted the entire transaction to go forward, without one of either the export or import legs being cut (failing to clear), it lumped the two deals together as a single “wheel-through” transaction under CAISO practice, so if a piece of the transaction didn’t clear, the entire deal would be cut.

In truth, however, the combined deals didn’t qualify under CAISO’s tariff as wheel-throughs, as the ISO tariff reserves that category for transactions that move power across CAISO from one intertie point to another, but with source and sink both occurring outside the ISO. And so because these physical transactions apparently violated CAISO’s tariff, and eventually turned out to be money-losing, FERC’s enforcement staff alleges them to be fraudulent—part of a circular scheme of physical trades devised primarily to capture revenue in a wholly separate financial derivatives market: from the export-direction CRRs held by Deutsche Bank.

And in an interesting twist, Enforcement bolsters its case by pointing out the notable coincidence that the DBET trader assigned initially to acquire a financial interest in ISO congestion rights was allegedly the same person who, in a previously life, wrote the software for the ISO’s CRR market. (DBET claims however, that the trader only created the CRR software interface, not the algorithmic “engine.”)

Yet the evidence also tends to show that the ISO might have wrongly advised DBET and other market participants early on that this combination of export and import trades would indeed qualify as a wheel-through under CAISO practice. As the defense claims, ISO employees seemed not to be familiar with the exact terms of the wheel-through tariff, as the ISO’s Business Practice Manual (since modified) appeared to allow what DBET was doing.

Consider this excerpt (See DBET Exhibit G) from a transcript of a telephone call between the ISO and an unnamed, third-party market participant, from May 2009:

Market Participant: Hey. So, I had a question … if I wheel some power, can I export and then import it back in? Or … does the wheel have to go me importing it and then exporting it back out?

CAISO: Yeah, you can export it and then import it back out. … we have a lot of that.

Market Participant: I’m looking to export at Palo … and then import it back in at Westwing.

CAISO: Yeah, I’ve never seen us not allow it.

According to another telephone transcript (DBET Exhibit H, from March 2010), another market participant had asked about how to tag a certain transaction—“when we do a wheel, which is, you know … an import and an export tied together”—and the CAISO employee on the other end had answered, “We’ve done this for a few months now and they’re always approved.”

Yet by June 2010, when the ISO referred the case to FERC enforcement for investigation (DBET Exhibit L, p. 14), the ISO was accusing DBET of circular scheduling, which itself was seen as a fraudulent practice:

“The circular nature of these imports and exports is inconsistent with ISO and FERC market rules prohibiting submission of false information and/or manipulation.”

For its part, Deutsche Bank denies any charge of circular scheduling, pointing out that the E-Tags show only the exports at Silver Peak, the transmission across Sierra Pacific Power to Summit, and the imports at Summit, and arguing that the ISO’s market monitoring department might’ve erroneously inferred the circular schedule from DBET’s apparently improper use of the wheel-through designation. (See DBET Answer, pp. 66-69.)

As for whether Deutsche Bank’s physical trades were profit-seeking, the evidence is dramatic. Note first that in June 2010, the ISO’s initial report referring the matter to FERC’s Enforcement Office (DBET Answer, Exhibit L, pp.3, 10) had identified some $42,000 in trading profits. Five months later, however, in November 2010, when the ISO’s market monitoring department sent a follow-up referral letter to FERC, the DMM identified a DBET trading loss of about $6,800. (See DBET Exhibit M, p.7.)

As Shanker observes, that late correction came only because it took that long for the ISO to process and issue all pertinent invoices:

“Given the CAISO DMM’s apparent difficulty in determining the profitability … the traders’ misunderstanding is not surprising.”

Software Going Rogue

Now consider Figure 2, which is taken from the Hogan affidavit in the Deutsche Bank case.

At a thinly traded intertie like Silver Peak, as depicted in the figure, the supply and demand curves won’t appear as gently sloping continuous lines that intersect, but rather, as discontinuous stair-step functions, as is shown on the right-hand side.

That makes it problematic to calculate the market-clearing price, as the supply and demand curves don’t even meet.

Instead, as Hogan explains in his affidavit, Figure 2 depicts a hypothetical degenerate pricing situation where an LMP price anywhere between $15 and $50 would solve the least-cost dispatch solution, and would serve in theory as an efficient and correct market-clearing price.

The actual situation in the Deutsche Bank was similar, but with slightly different numbers: $70 (rather than $50) for the lowest-cost supply bid (import bid), and $55 (rather than $40) for the market price in CAISO.

Also, in the actual case, the ISO had imposed an import transfer limit at Silver Peak of 0 MW, meaning that no import bid could clear, as no additional imports could be scheduled without exceeding the transfer limit.

These facts would’ve created a degenerate price range of between $15 and $55: any market-clearing price within this range would be “efficient” and would satisfy the unique least-cost, security constrained dispatch solution.

But in this situation, according to the defense, the CAISO software defaulted to $15, the lowest price in the range, whereas it should have defaulted to $55, the system marginal energy cost of the most economic supply (an export from CAISO) that was eligible to satisfy an additional increment of demand at the Silver Peak node—the ISO’s tariff definition of LMP. And this reasoning seems to be backed up by a review of congestion pricing at Silver Peak, presented by Eric Hildebrandt, director of the ISO’s department of market monitoring. (See DBET Exhibit N.)

If all this sounds a bit convoluted, the reader might well prefer the much shorter narrative given by consultant Roy Shanker, testifying for the defense:

“The software is running the show, pricing is arbitrary, and CAISO is not following … the market design.”

Derivatives on Trial

So how do we arrive at the notion, urged by the defense, that FERC’s investigation in the Deutsche Bank case threatens the foundation of markets?

First, understand that when the commission promulgated its current price manipulation rule, more than five years ago, it borrowed its definition of fraud from the same case-law precedent that prevails in securities regulation:

“The commission defines fraud generally, that is, to include any action, transaction, or conspiracy for the purpose of impairing, obstructing or defeating a well-functioning market.” (See Order 670, ¶50, Dkt. RM06-3, Jan. 19, 2006, 114 FERC ¶61,047.)

Under that definition, FERC need not prove an actual intent to manipulate prices. Instead, it could be enough simply to show that a transaction was conducted improperly, such as Deutsche Bank’s mistaken characterization of its physical transactions as “wheel-throughs.” Or even to show a coupling of unprofitable day-ahead trades (such as DBET’s physical schedules) with positions in financial derivatives (CRRs or FTRs), which could be interpreted as “impairing” or “obstructing” markets.

By contrast, the Deutsche Bank defense team argues that simultaneous trading in both physical and financial markets shouldn’t imply manipulation unless FERC can find that the actor was trading “against interest.” That test, the defense argues, is one that FERC has applied in the past. (See, DC Energy v. HQ Energy Servs, Dkt. EL07-67, Sept. 29, 2008, 124 FERC ¶61,295.)

In particular, however, Hogan suggests that FERC’s enforcement office is mistaken in its concern over simultaneous physical and congestion trading.

As Hogan explains, financial derivatives such as FTRs and CRRs are tied inexorably to the capabilities of the grid. They must be simultaneously feasible under the condition of the security-constrained, market-clearing, least-cost dispatch solution, or else they can’t be adequately funded by RTO-ISO LMP revenues.

Stated differently, FTRs and CRRs are grounded in physics and bounded by volume; thus, regulators shouldn’t view them in the same light, for example, as the credit default swaps that proved so toxic during the recent credit panic of 2007 through 2009.

In fact, this very real ceiling that the physical grid places on trading electricity congestion rights lies at the heart of why the Commodity Futures Trading Commission is now considering whether to grant a petition filed earlier this year by the nation’s ISOs and RTOs, seeking an exemption from Dodd-Frank requirements for FTRs and CRRs. (See, CFTC, Notice of Proposed Order and Request for Comment, 77 Fed. Reg. 52,138, Aug. 28, 2012.)

Yet Shanker fears the cat already is out of the bag, as he finds the implications of the Deutsche Bank case impossible to ignore:

“In my practice, since the commencement of the Enforcement investigation of the DBET trades, I have had to offer highly conditioned advice … to other parties seeking to execute what I would consider straightforward, profitable transactions.

“The chilling effect isn’t imagined; it is real and has already occurred.”