The competitive transmission genie is out of the bottle.

Elliot Roseman and Ken Collison are vice presidents at ICF International. Kiran Kumaraswamy is a senior manager at ICF.

The structure of the transmission industry is changing substantially, and will continue to do so for some time to come. With the advent of competition, there will be both legacy and new transmission players, with opportunities opening up for both progressive utilities and independent transmission companies alike.

How can we make such a statement? It's supported by strong precedent in power generation, as well as ongoing trends in the evolution of markets and business models.

Back in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the U.S. Congress heralded a revolutionary development, when it enacted the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act (PURPA). For the first time, the law obligated utilities to purchase generation capacity and energy from others rather than only build it themselves. These new upstarts - qualifying facilities (QF) or so-called "PURPA machines" - had to meet strict efficiency and size criteria. For QFs that succeeded in being built and coming on line, utilities were required to provide interconnection service and to calculate and pay the utility's avoided cost for their entire output.

PURPA was the camel's nose under the tent. By the mid-1980s PURPA catalyzed a massive influx of offers from non-utility generators (NUG) to sell power to the utilities, to such an extent that some utilities couldn't absorb them all. Interconnection became a major issue. Some states adopted payment approaches (e.g., New York's "6-cent law") that seriously cut into utility profits, and utility credit ratings began to suffer. There was talk of repealing PURPA, but it had solid political support.

What to do? Faced with barbarians at the gate, the utilities came up with a brilliant solution: make the NUGs compete, not with the utilities' cost, but with each other. They started to issue RFPs that identified their capacity needs, timing, and types of power required. Early on, through trial and error, utilities discovered that they needed to set threshold criteria for bids, such as requiring that they have features like a reliable fuel supply and a contracted site. Within just a few years, a number of states (e.g., Massachusetts, Minnesota, Wisconsin, etc.) had adopted approaches to evaluate bids for capacity, and to accept only those that were deemed best using a complex array of criteria. Also, the utilities also figured out how to participate in their own solicitations, using independent evaluators or separating the evaluation from the bids. Using this approach, hundreds of thousands of megawatts were offered to utilities; tens of thousands of megawatts were selected; and most (but not all) of the selected projects signed contracts and were built; some failed to secure air permits or financing.

Figure 1 - Utilities Creating Merchant Transcos

Figure 1 - Utilities Creating Merchant Transcos

The Energy Policy Act of 1992 (EPAct) gave a whole new meaning to this competition by allowing independent power producers (IPP) that didn't meet PURPA's efficiency standards to compete head-to-head with utilities to supply baseload generation. At this point, utilities set up their own unregulated IPP affiliates to mirror the young upstarts and compete outside of their service territories. Examples included Southern California Edison (Mission Energy), Duke (Duke Energy North America), PG&E (PG&E-Bechtel, which later became U.S. Generating Co.), Xcel Energy (NRG Energy) and others. Some went overseas as well, mostly with disappointing results before they returned to the United States. The rest is history. Between RFPs for new generation and the conversion of rate-based generation to unregulated units, IPPs now make up 35 to 40 percent of all power generation and capacity in the U.S.

Fast forward again. FERC issued Order 1000 in July 2011, and this time, competition came to the transmission business instead of generation. This seminal Order - along with requirements in Order 890 - required all regions of the country (both traditional and organized) to develop or demonstrate an approach to transmission planning that included "non-transmission alternatives," (NTA), and eliminated the right of incumbency at the federal level by quashing the "right of first refusal." FERC Orders 890 and 1000, it seems, are the PURPA and the EPAct of transmission, as we are now seeing regional markets such as PJM, Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO), and California ISO (CAISO) adopt methods to allow competition to build and own transmission.

Just as no one thought that direct competition was possible for generation until PURPA, few thought it was possible for transmission until FERC Orders 890 and 1000. Also, decades of planning experience combined with these orders has shifted the focus from the individual utilities to the regions and RTOs, which also changes the location of where costs and benefits are assessed.

One hopes we've learned from our earlier experience. Rather than let a transmission tsunami wash over them with random offers to build and pay for new lines, the RTOs and ISOs are proactively organizing competitive processes to meet their reliability, economic, and public policy needs. They know from generation's hard experience that they need to qualify transmission bidders, based on both their prior experience and financial wherewithal.

Figure 2 - PJM Artificial Island Proposal

Figure 2 - PJM Artificial Island Proposal

Now the question is: what does competition for transmission portend for industry participants, and how could it change the game for regional entities, incumbent utilities, and their customers?

Proving Transmission Needs

As utilities and system operators prepare for the new landscape in transmission system procurement, they must contend with some issues that parallel those associated with the QFs and IPPs of the 1980s and 1990s, but they also must address a host of issues unique to transmission, and which bring with them significant technical and financial challenges. These relate to both the scale and complexity of these projects, as well as the specifics of power flow on the bulk power grid.

For example, because of the long lead times required to develop new transmission projects, it isn't unusual for system planners to initiate the process to meet reliability needs that are 10 or more years in the future. This presents a challenge, because ever-changing system supply and demand conditions and NTAs can lead to modified transmission project scope, extended timelines, project suspension, and even cancellation. For example, in 2012 PJM cancelled the Potomac Appalachian Transmission Highline (PATH) and the Mid-Atlantic Power Pathway (MAPP) because the recession, lower load growth, and demand response offers showed that they were no longer required to maintain grid reliability. These cancelled projects, valued at over $3 billion, were first proposed in 2007 and later approved by PJM in its system plan.

Transmission projects that are part of the emerging competitive solicitations, as described below, are subject to all of the same vagaries of the market and the resource planning process. Of course, the same factors affect power generation, but because of the shorter lead time and fewer permitting challenges, power plants are more likely to proceed than major transmission lines.

Figure 3 - PJM 2013 Market Efficiency Proposal Respondents

Figure 3 - PJM 2013 Market Efficiency Proposal Respondents

The process will further be complicated by the need to consider NTAs. Lessons from regions that already have similar requirements shows that this will introduce another layer of complexity and can change the scope of a proposed transmission project. In New England, a project proposed to meet a regional reliability need will be approved for construction only if it's shown that options such as NTAs can't solve the reliability problem and displace or defer the line. In Southern New England, National Grid and Northeast Utilities performed extensive studies to demonstrate that the New England East West Solutions (NEEWS) projects were preferred to NTAs. In Maine, the NTA analysis contributed to a change in scope from the transmission solution that was originally proposed as the Maine Power Reliability Program (MPRP).

In light of these challenges, it's clear that transmission procurement in a post-Order 1000 world will need to incorporate measures that account for changing system conditions and other development challenges that can defer if not eliminate the need for the project.

Transco Models

The new transmission environment ushered in by Order 1000 creates new challenges and opportunities for incumbents, other utilities, and independent transmission firms. For example, the order requires system operators to establish criteria that aren't unduly discriminatory for potential developers to demonstrate their capability to develop transmission facilities. Such a process, already being implemented by the PJM and California ISOs, will place incumbent utilities and interested transmission developers on equal footings to develop and own transmission projects. Similar to industries like telecom, opening the door to other market participants and encouraging competition is intended to create higher levels of efficiency, encourage innovation, and keep costs down.

Transmission-only and transmission-focused firms such as Trans-Elect, ITC, ATC, Anbaric, Pattern Energy, LS Power and others have been in the market for years, and with this boost from Order 1000, such transcos could have several advantages. For example, being part of an independent transmission company can eliminate the appearance of conflicts. In addition, transcos can: eliminate competition for capital from generation and distribution investment priorities; provide a singular staff focus on the challenges of transmission development; and create scale in all facets of such development (e.g., permitting, financing, construction, etc.).

Figure 4 - Structure and Bidders in CAISO Solicitations

Figure 4 - Structure and Bidders in CAISO Solicitations

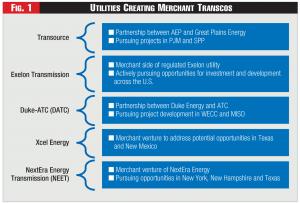

In line with such potential benefits, utilities like AEP, Exelon, Xcel, and Duke Energy have established transcos to pursue opportunities arising from Order 1000 and to expand their footprint beyond their regulated service territories (see Figure 1). In some cases, these transcos have a specific target area (e.g., Xcel will be focused on developing transmission in Texas and New Mexico). Duke's venture with American Transmission Company, DATC, purchased 72 percent of the capacity on Path-15, a major transmission corridor from northern to southern California in April 2013. The company also is pursuing projects in the Midwest and Pacific Northwest.

As another example, in early 2013 utilities in New York created a one-of-a-kind proposal to establish a public-private transco to accelerate the investment of billions of dollars into the state's grid to replace aging infrastructure and fund system upgrades. This model for large-scale infrastructure investments underscores the financial prudence of rolling transmission assets into a separate entity for ease of regulatory treatment and access to capital markets. Although the deal didn't go through, ITC's move to purchase Entergy's transmission assets reflects a similar philosophy to promote investments in the region under a different ownership structure. At the same time, some such ventures have ended, such as when AEP and MidAmerican announced their plans in December 2012 to end their 50-50 partnership (Electric Transmission America) that successfully developed the Prairie Wind project in Kansas.

Overall, these examples illustrate that the business models for developing transmission are beginning to change to allow competition and growth in the new age launched by Order 1000. We expect that such restructuring will continue with other utilities and transmission owners across the country in the near future.

Rising Competition

Over the last six to nine months, utilities and system operators have conducted a handful of competitive solicitations, with substantial interest from transcos and independent developers, including international firms, to develop, build and own transmission lines. In the near-future we expect a continued high level of transco participation in such solicitations.

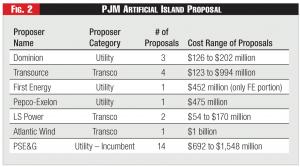

In April 2013, PJM issued one of the first of these solicitations to address technically challenging reliability concerns at an "artificial island" near the Salem and Hope Creek nuclear plants. This was an open solicitation that allowed bidders to determine how to respond to solve the reliability concern. In response to this solicitation, PJM received 26 proposals from seven entities that included three transcos - LS Power, Atlantic Wind, and Transource (Figure 2). The proposed solutions ranged widely in cost, from $100 million to $1.5 billion. PJM is evaluating the proposals with respect to cost and their effectiveness at addressing the reliability problem.

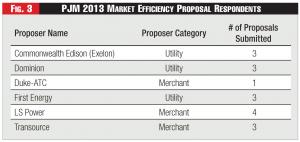

The second solicitation from PJM addressed market efficiency issues to provide relief for the top 25 congested facilities and interfaces in PJM, and solutions for interregional congestion issues. In response to this solicitation, six entities submitted 17 proposals with a range of projects including upgrades to existing facilities to provide congestion relief (Figure 3). Merchant companies submitted strong proposals, some of which scored well in the benefit-to-cost analysis that the technical committee of PJM performed late last year.1 This is an indication that the market is open to innovative solutions to address grid congestion as well as reliability challenges.

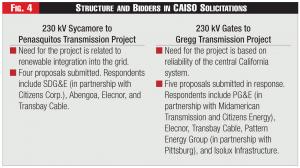

Outside of PJM, last year CAISO issued two requests for proposals related to reliability and renewable integration needs in their system. Both of these were closed RFPs, in that CAISO requested bids to build transmission from one point to another, with a specific voltage capacity, and with less opportunity for flexible responses than the PJM RFPs provided. The market responses to both these requests were considerable, as several merchant companies (including international firms such as Abengoa, Isolux Corsan, and Elecnor) joined the incumbent utilities and others to bid into the process to build, own and operate the transmission lines (Figure 4). The international companies have significant expertise in developing transmission assets globally and are trying to leverage such experience to penetrate the market in North America.

In the Gates to Gregg RFP, in November, 2013, CAISO selected the incumbent, PG&E, along with its partners MidAmerican and Citizens Energy as the winner, showing the value of incumbency, particularly in closed solicitations.

Innovation Benefits

Following in the footsteps of generation in decades past, the competitive transmission genie is out of the bottle, and it's not going back in. Increasingly the industry will use competitive solicitations to develop transmission in the U.S., driven in no small measure by FERC Orders 890 and 1000. The response to solicitations in the PJM and California markets demonstrate a strong interest by transcos in competing with the incumbent utilities to develop and own transmission assets. Just as in the era of PURPA and EPAct, utilities are in the process of establishing subsidiaries to position themselves for emerging opportunities in new areas. Along with the influence of non-utility transcos, this competition likely will lead to creative solutions, efficiency gains, cost savings, and structural changes that will reshape the transmission landscape and benefit consumers from this point forward.

The extent to which customers get their wishes granted by this new genie remains to be seen, but if competitive dynamics and the evolving solicitation processes work, they will see real benefits from the invisible hand of the market.

Endote:

1. As an example, two of the proposals from LS Power passed the cost-benefit test, based on preliminary results presented at the PJM Transmission Expansion Advisory Committee Meeting, Dec. 11, 2013.